Can More Information Create Polarization?

Why It Is Important to Know the Sources of Disagreement

To say that people routinely disagree is an understatement, especially in contemporary liberal democracies. While disagreement is a normal fact of life, too much disagreement can become a problem, especially when it makes cooperation more difficult to achieve and creates costly conflict. There is a long tradition in economics that locates the roots of disagreement in differences in information and the dispersion of knowledge in society. In other words, people disagree because they don’t know the same things and don’t have access to the same information. This is a relatively optimistic outlook because if people really disagree because they don’t have the same information and knowledge, there is a really straightforward solution to reduce the level of disagreement in society: just educate them and give them more information. Unfortunately, things are not so simple.

The idea that disagreement is essentially due to differences in information and dispersed knowledge is especially well-captured by a theorem established by the economist and game theorist Robert Aumann.[1] This theorem establishes that under some conditions, rational individuals cannot “agree to disagree.” I present a stylized version of Aumann’s agreement theorem at the bottom of this post, but for readers who only want to understand the general idea, here is an explanation in plain language (at least, as plain as it can be).

Consider two individuals who have to form beliefs about a series of events, e.g., the fact that the Golden State Warriors will win the 2023 NBA Finals, that Macron will give his pension reform, or that the stock market will crash in the next six months. Each individual starts with “prior beliefs”, that is, beliefs based on what one knows given the information at her disposal. Now, suppose that the two individuals meet and state their prior beliefs. They thus learn each other’s opinions. These opinions, therefore, become common knowledge: both individuals know that they know that they know… everyone’s opinion. Learning the other’s opinion is in itself new information that one should rationally use to revise her prior belief. Obviously, because opinions are common knowledge, the two individuals now have the same information at their disposal. Aumann’s agreement theorem demonstrates that in these conditions, the two individuals’ opinions (i.e., their “posterior beliefs”) must be identical. They cannot agree that they disagree.

For the theorem to apply, several assumptions must be verified. Three of them are explicit. First, agents must be “Bayesian rational.” That means that upon learning something new, they must revise their beliefs using Bayes’s rule of conditional probabilities. In other words, an individual’s belief that some event E will happen must be a probability, and the probability that E happens (e.g., the Warriors will win the NBA Finals) given the information I received (e.g., the Warriors didn’t qualify for the playoffs) must be equal to the ratio of the probability that E and I (obviously, this is 0 in this example) happen at the same time divided by the probability of receiving I. Second, the agents’ prior beliefs must be identical, they must have a “common prior.” That does not mean that they must have the same opinion from the very beginning. It is rather that if they had the same information from the start, they couldn’t disagree. This is a very strong assumption that it is directly responsible for the result of the theorem. Third, agents’ posterior beliefs must be common knowledge, as described in the preceding paragraph. The last assumption is only implicit and states that agents when learning others’ opinions, learn everything that others already know. It is as if one’s opinion was transparently synthesizing all the information on which the opinion is based.

Aumann’s theorem leads to some strange results. For instance, it indicates that on financial markets people should not be willing to make any trade. After all, if someone is willing to sell me some asset A at a price p, that means that he must have some information that the price of A will fall and/or that there are better investment opportunities for the money that A is worth. But then, as a Bayesian rational agent, I should revise my belief that A is worth p and decide to not buy A at this price.

The fact is that while the theorem is valid (it is true mathematically speaking), it rarely applies in reality. The most obvious reason is that there is no reason to assume that people have a common prior. After all, it seems that very often, disagreement does not disappear even when everyone has access to the same information. This is only half an explanation however because this doesn’t specify what are the other sources of disagreement than differences of information. A widespread source of disagreement is however that, independently of what people might believe, they do not perceive events in the same way. In other words, they do not share the same perspective on the social world. Some philosophers call this phenomenon “perspectival diversity.”[2]

Consider for instance people’s views about the permissibility of abortion. People might eventually agree that while women’s bodily autonomy matters, this is trumped by the requirement to respect and save the life of a human being. Even in this case, individuals will disagree on the issue of abortion if they do not share the same perspective about what counts as a human being. If I consider that a 12-week-old fetus is not a human being, I’m likely to regard abortion as permissible. If you do consider that a 12-week-old fetus is a human being, you will oppose abortion. It is easy to adapt the example to account for disagreement about the moral status of pornography (whether or not someone perceives that pornography harm women’s condition in society) or individual responsibility (that someone should be helped may depend on whether she is perceived as being responsible for her situation).

Why is it important to acknowledge the role of perspectival diversity to explain disagreement? There are two related aspects that are salient. First, it is plausible to assume that perspectives are fixed over the short and mid-term. Perspectives are related to factors such as religion, ethnicity, gender, language, and political ideology that are, for the most part, largely out of the control of individuals. Perspectives may change but it takes time. As far as individual behavior and social practices are related to perspectives, recent economic studies about immigration suggest that they are enduring and that actually immigrants carry their way of life to their new country and that this last over several generations.[3] That means that while individuals can learn new things through information provision and education, their perceptions are far more difficult to change. As I show in the formal section below, once you add perceptions in Aumann’s framework (through the concept of “cognitive partitions”), the kind of convergence of knowledge that explains why people cannot agree to disagree is blocked by perspectival diversity. Second, and more counterintuitively, it can be suggested that in some cases, providing more information will not reduce but reinforce disagreement. This is due to the fact that spreading and sharing more information will exacerbate disagreement by making more salient the fact that disagreement is based on fundamental beliefs that persons take to be constitutive of their personal and social identities. This seems to be confirmed by facts. There has never been so much information available but at the same time, Western societies have rarely been so polarized. This might be due to the fact that these societies are more and more open, leading to an increased level of perspectival diversity.

************************

Appendix

Here is a more formal treatment of the idea developed above. It illustrates Aumann’s agreement theorem through a simple example and shows the consequence of adding perspectival diversity to the model.

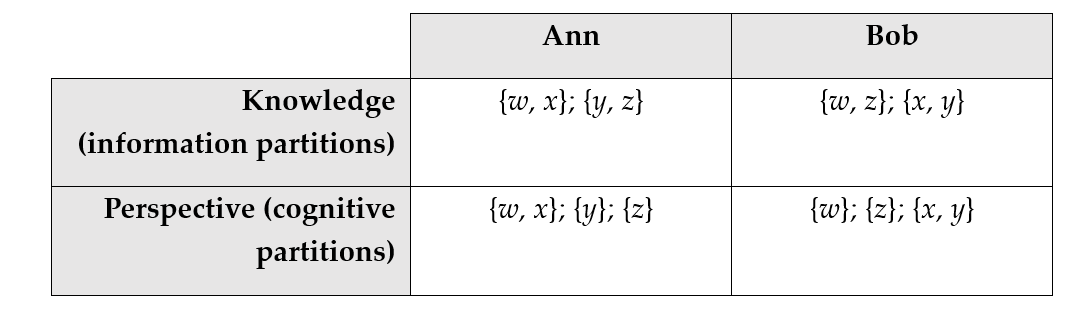

We assume a state space and two persons, Ann and Bob, endowed with different information. Let us suppose that Ann and Bob have a common prior p = ¼ for each social state. Ann’s and Bob’s knowledge is captured by the information partitions indicated in the following table.

Suppose that x is the actual state of the world. Given their information partitions, Ann will learn that either w or x is the case and ascribe a probability of ½ to each. Similarly, Bob will learn that either x or y is the case and ascribe a probability of ½ to each. If these posterior beliefs are commonly known by Ann and Bob, both will conclude that w and y cannot be the case and will therefore know that x is the actual social state. Here, Ann and Bob clearly cannot agree to disagree. The addition of cognitive partitions changes however the conclusion. From Ann’s perspective, there are only three social states: w/x, y, z. The information at her disposal excludes the last two and she therefore “knows” that w/x is the case. Similarly, Bob “knows” that x/y is the case. Now, upon learning each other’s opinions, it seems clear that Ann and Bob are not in agreement. Their respective knowledge is mutually inconsistent because it cannot be possible that both w/x and x/y are both the case. Ann and Bob fundamentally disagree on the features of the social world that they know to be the one in which they are living.

This example illustrates a general result. The “convergence” of opinions that happens when Aumann’s Agreement Theorem applies is due to the fact that agents who learn others’ posterior beliefs update their information partitions. This is what happens in this example without cognitive partitions. When Ann learns Bob’s opinion, she refines her partition from {w, x} to {x}, and similarly for Bob who refines his partition from {x, y} to {x}. In general, the fact that posterior beliefs are common knowledge results in agents’ partitions sharing at least the common “cell” to which the actual state belongs. Combined with the common prior assumption, this implies that agents must share the same posterior beliefs for all states within that cell. However, because cognitive partitions override information partitions, the convergence of opinions is blocked if it happens that the agents’ cognitive partitions do not overlap with this common cell.[4] We can note moreover that perspectival diversity makes the common prior assumption more difficult to interpret because agents cannot have well-defined priors on social states that are not singleton in their cognitive partitions. It essentially becomes a notational artifact, as in the example given above.

[1] Robert J. Aumann, “Agreeing to Disagree,” The Annals of Statistics 4, no. 6 (November 1976): 1236–39.

[2] See in particular Ryan Muldoon, Social Contract Theory for a Diverse World: Beyond Tolerance (Taylor & Francis, 2016).

[3] See especially Garett Jones, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move To a Lot Like the Ones They Left, (Stanford, California: Stanford Business Books, 2022).

[4] In the example given in the main text, the common “cell” is {x}. But Ann’s and Bob’s cognitive partitions put social state x in a cell that contains another state, w for Ann and y for Bob.