Christmas and the Ontology of Rule-Following

What does it take to follow a rule? More generally, what are rules? These are deep questions that have attracted great thinkers working from many different perspectives, from Wittgenstein to Kripke, from Rawls to Hayek, from Lewis to contemporary game theorists. Let me add my modest contribution to this literature, taking Christmas as an opportunity to illustrate my conception.[1]

I start with some generalities. We call an event E a state of affairs that corresponds to a proposition that is true in at least one possible world. For instance, “Today we are the 24th of December” is such a proposition that happens to be true today, in our world. A person has reason to believe that E just in case, in light of the information and the background knowledge this person has, she has sufficient reason to think that the proposition corresponding to E is highly likely to be true. There is mutual reason to believe that E in a given population P just in case everyone in P has reason to believe that E. Finally, we say that E is a public event in P when there is common reason to believe E in P. That is, everyone in P has reason to believe that everyone has reason to believe E, everyone has reason to believe that everyone has reason to believe that everyone has reason to believe E, and so on ad infinitum.

Now, suppose that as it happens, there is in P mutual reason to believe that E. Suppose that the members of P are symmetric reasoners with respect to E. By this I mean that given their background knowledge, members of P use the same kind of (inductive) reasoning with respect to E. In particular, we suppose that each member of P makes an inductive inference from E such that, if one has reason to believe E, then she also has reason to believe that there is mutual reason to believe E in P. Moreover, we assume that each member of P also makes another inductive inference from E to an event F, i.e., if one has reason to believe that E, then she also has reason to believe F. More formally, using BE, ME, BME, and CE for “reason to believe E”, “mutual reason to believe E”, “reason to believe that there is mutual reason to believe E”, and “common reason to believe E” respectively, and using the arrow → to denote the inductive inference, we have

(1) ME in P.

(2) BE → BME and BE → BF in P.

Then

(3) CF.[2]

Basically, what this shows is that if everyone in some population is a symmetric reasoners with respect to some event E and that everyone makes the inferences (2) from E, then there is common reason to believe F in this population. This account of “common knowledge” is due to David Lewis. It is very interesting because it shows how a proposition can become commonly known based on a shared mode of reasoning.

Now, if you substitute F for any behavioral pattern where each person acts in some specific way, the above reasoning indicates that everyone will infer that there is common reason to believe that this pattern will emerge as soon as there exists a “common reflexive indicator”, i.e., some event E, that everyone has mutual reason to believe in the population. I would suggest that the essence of rule-following lies there. To follow a rule is just to infer from a given state of affairs what I ought to do – both in the practical and normative sense. This inference is grounded on background knowledge and a mode of reasoning that everyone assumes – not intentionally or at least not consciously – to be shared in the population. We obviously have reasons to believe that many propositions are true at each moment in our environment. The fact that a given event E triggers the reason to believe that there is common reason to believe another event F singles it out, it makes it “salient”. Event E has a special psychological status in virtue of the fact that we take it for granted that it grounds another public event F. And because the rule that links E to F in such a way indeed holds in the population, the inferences we make and the expectations we form on their basis are right.

But where this symmetric reasoning comes from? At this point, as far as social ontology is concerned at least, there is no further answer to give. Following rules is just what Wittgenstein refers to as a “form of life”. We just happen to follow rules, and to follow rules is just to make the same practical inferences based on a subset of events. For sure, social sciences, cognitive sciences, and history have plenty of things to add to this ontological view. For each specific rule, there are historical, cultural, economic, and political circumstances that can account for why we are following this rule. The so-called “theory of mind” also largely contributes to a better understanding of the cognitive mechanisms sustaining what I have called symmetric reasoning, for instance.

So, let’s return to Christmas. Christmas is an institution in many cultures, in the sense that it corresponds to a set of rules that people happen to follow. Among those rules, there is one of the core ones according to which, on a definite day (not necessarily the same everywhere), people form expectations about the fact that others will offer them gifts and will have reciprocal expectations. There is common reason to believe that everyone has these expectations and that they will be fulfilled. Santa Claus may not be real, but the power of rules to generate common reason to believe is surely even more fascinating than this mythical figure!

**********************************

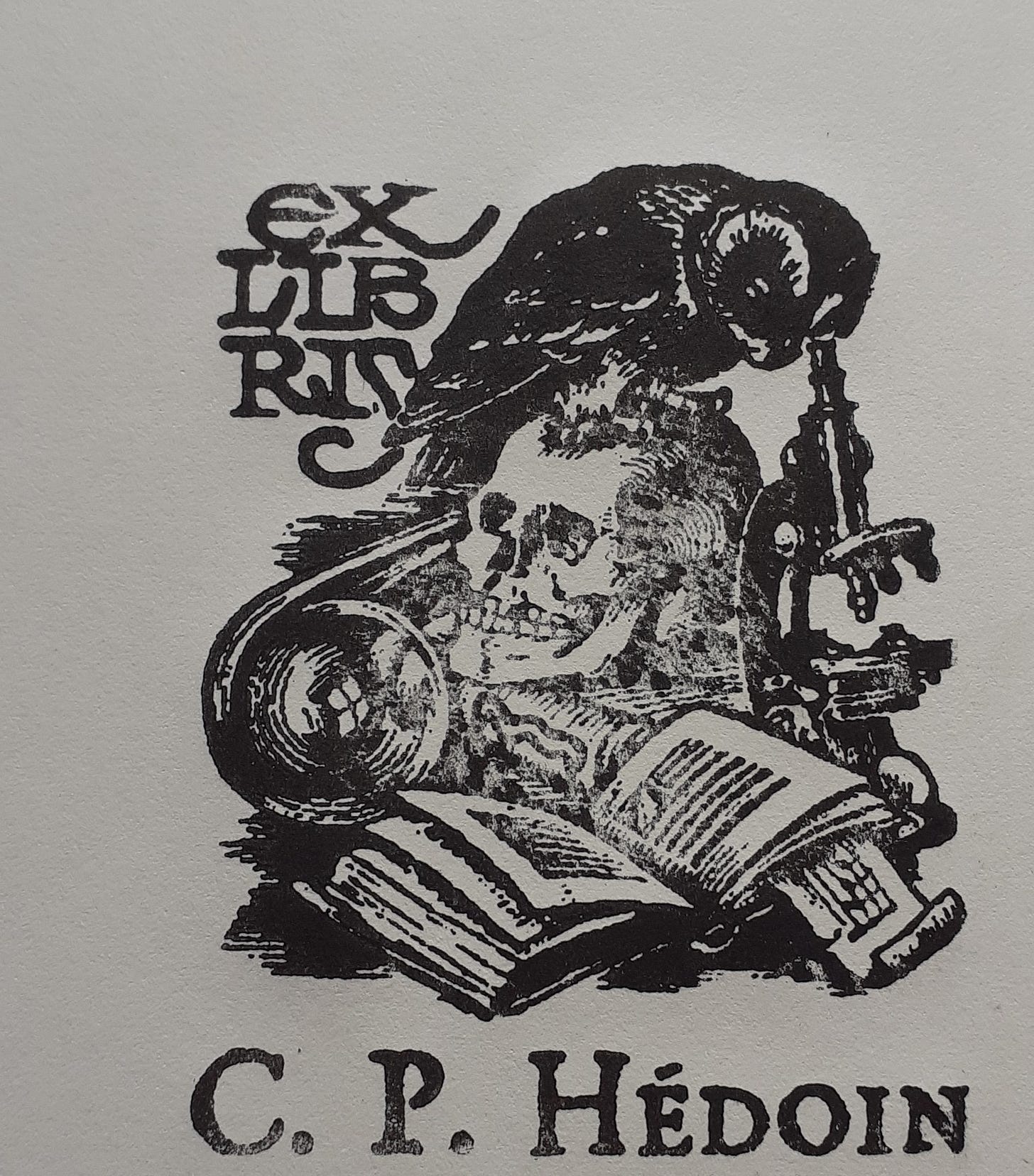

As for me, Santa Claus has already brought some gifts, among which probably one of the most original I have received, a personalized ex libris. Big thanks to Eva!

Joyeux Noël, Merry Christmas, and as I’m spending this Christmas in Slovakia, veselé Vianoce!

[1] Most of what follows is based on ideas I’ve developed in several published articles, especially my 2017 paper in Economics and Philosophy¸ “Institutions, Rule-Following and Game Theory”.

[2] See David Lewis, Conventions (1969), p. 47.