Evolution and Politics

On the Evolutionary Roots of Human Politics and Their Implications

Very short summary: This essay discusses the view that the naturalistic origins of politics set limits on what it can achieve. I argue that this view can sensibly be included within a broader realist approach to politics. However, I also emphasize that our limited knowledge of how and to what extent our evolutionary history really shapes politics must be duly acknowledged. In particular, the “evoconservative” claim that morality is constrained in its inclusivity is politically problematic. Politics should not coerce people in the name of progressive fantasies, nor in the name of an elusive human nature.

There are many possible definitions of what we call “politics,” and arguably none is consensual among political scientists and other specialists. My preferred one would, however, run something like this: the art of (re)designing society by choosing and altering the rules that justify coercive interferences with people’s lives, and of acting based on those rules in the pursuit of a large range of diverse goals that are supposed to transcend individual interests. Politics is about designing the rules of society at various levels, from the top (constitutional rules) to the bottom (e.g., rules for the provision of local public goods), and acting based on them. What differentiates politics from mere engineering is that this designing endeavor appeals to a complex mix of values (or principles, goals, ends) and facts (or means). A more specifically liberal perspective on politics turns this definition into the statement of what is sometimes called the “constitutional problem”: how should society be organized so that individuals can freely live the lives of their choice while avoiding turning into chaos?

Associating “politics” and “design” can understandably raise concerns. First, it grants political designers a lot of power over the rest of us. By determining when coercion is legitimate, they acquire potentially extensive control over people’s lives. To contain the risk that this power might be abused, the design must be such that the rulers and the ruled are, if not the same persons, at least mutually checking each other. This is the ideal of self-governance. Second, even if this ideal is close to being realized, there are still many ways the designing endeavor can go wrong. After all, humans are fallible, their knowledge is limited, and they may become carried away by their ambitions—what is known as “hubris” and what we, French, sometimes call “la folie des grandeurs.” Now, whether we like it or not, this is what sets human politics apart from other “animal politics,” the latter being purely spontaneous and (almost) entirely determined by genetic factors. Humans are intentional beings with a highly developed capacity to plan, a capacity that is enhanced by language and culture.

In this perspective, one specific risk is that human politics forgets and turns against its naturalistic origins, as former New York Times journalist Nicholas Wade documents in his recent book The Origins of Politics.[1] This is a fair concern. Recent human history is full of ambitious political attempts to transform, if not destroy, long-standing human institutions rooted in our evolutionary history, such as the family. The case of the kibbutz system with which Wade starts the book provides a vivid illustration of the damages that such misguided political designs can produce. Wade’s book makes the case that the naturalistic origins of the family, tribalism and nationalism, sex-based division of labor, and warfare cannot be ignored by human politics, at the risk of destroying societies—for instance, by leading to a dramatic decline in birth rates.

As is always the case when appeals to “human nature” are made in debates over moral, political, or cultural issues, the naturalistic fallacy is never far. It’s not because a trait has evolved that this trait is “good,” “desirable,” or “justified.” Evolution is normatively blind. Traits (or their underlying genes) are selected according to their (inclusive) fitness, and there is no logical relationship between fitness (a purely empirical concept) and morality or any normative concept. The same applies to the institutions (the family, the nation, religion) that evolution has indirectly given rise to. That an institution has evolved does not make it good or right.

However, the naturalistic fallacy can be avoided, and Wade mostly succeeds in this. Evolution cannot justify anything, but it can plausibly set empirical constraints on what human politics can achieve. In this sense, naturalistic accounts of politics such as Wade’s are part of the broader political realism movement that urges political theorists and philosophers to give up idealistic accounts of politics that disregard feasibility constraints. Politics is not practiced in a biological and social vacuum. Political design must properly account for human motivations and provide the right incentives. Individuals’ objectives and beliefs can be influenced, but only up to a point. Interests and passions have long-lasting genetic roots. The practice of human politics itself, though it has evolved quite distinctly from other animal politics, is not detached from its evolutionary origins. The need to form “coalitions to control a society’s institutions in ways conducive to its survival” is part and parcel of human politics and something we plausibly have in common with our close cousins, the chimpanzees.[2]

Therefore, I generally agree with the idea that politics, both in its analysis and its practice, should be conceived from a realistic perspective that includes naturalistic elements—not to justify or condemn institutions per se, but to be mindful of what political design can achieve, how it can achieve it, and what the risks are if feasibility constraints are ignored. To put it in more economic terms, as with all human activities, politics is subject to incentive-compatibility and participation constraints, and part of these constraints are definitively tied to our evolutionary origins. Now, and this is what makes the realist perspective particularly appealing, arguments about feasibility constraints can partly be empirically assessed, which makes it possible to detect when evolution is used with an ideological purpose.

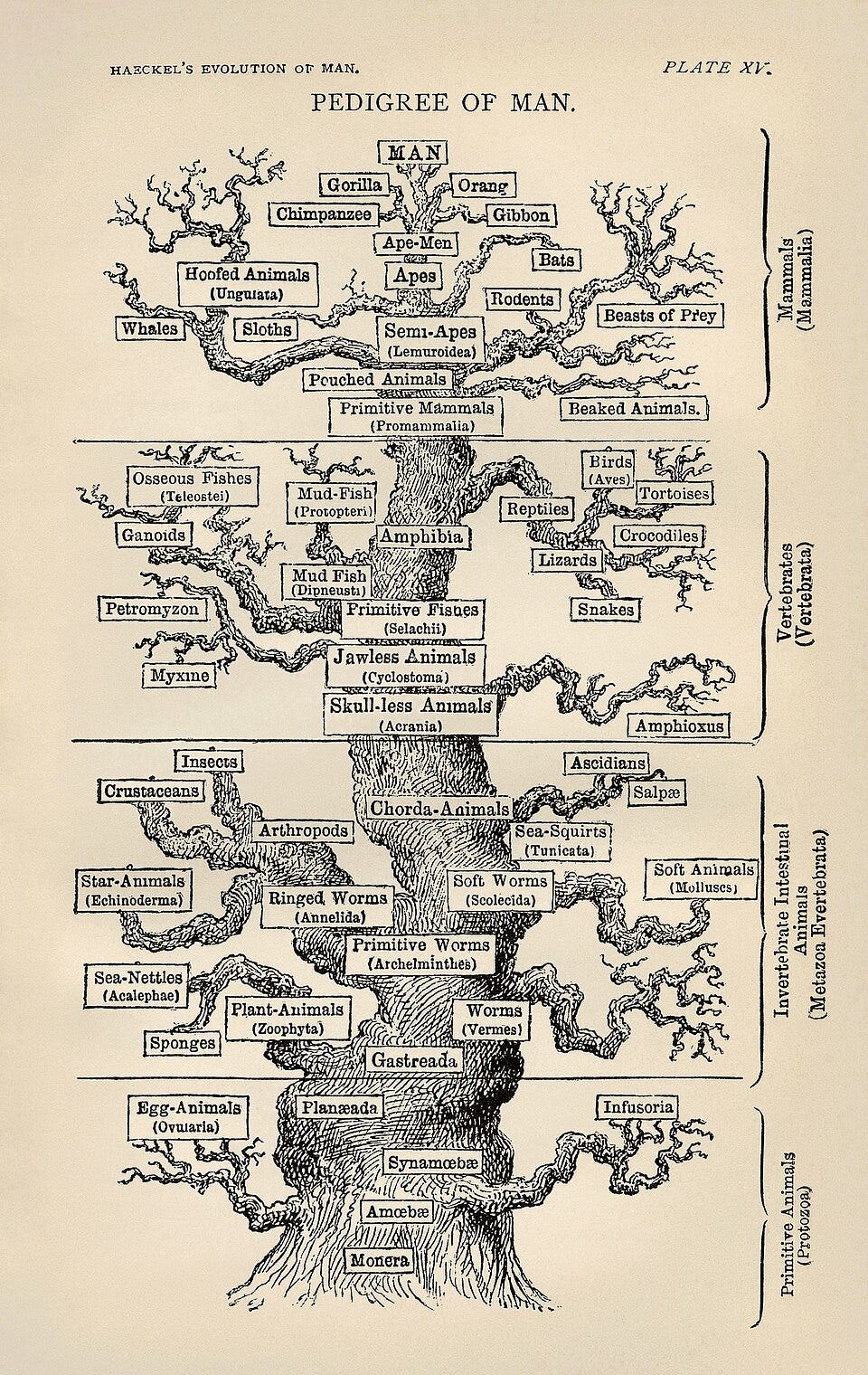

Ernest Haeckel’s tree of life, The Evolution of Man (1879)

Even if he denies that his arguments vindicate “conservatism” over liberal politics, Wade’s book is an instance of what philosophers Allen Buchanan and Russell Powell call evoconservatism, an intellectual trend that has gained significant influence over the last couple of decades.[3] Evoconservatism is well represented by academic figures like Jonathan Haidt, Joshua Greene, Eric Posner, and Jack Goldsmith. There are several versions of evoconservatism, but the basic idea is that the evolutionary nature of morality sets severe constraints on its content. In particular, attempts to make morality more “inclusive” by extending its authority beyond the circle of genetic and, eventually, cultural relatives are doomed to failure because they go against the natural inclinations of humans inherited from their evolutionary history. The main tenets of evoconservatism can be summarized as follows:

1) The evolutionary origins of morality correspond to a very specific environment—the “environment of evolutionary adaptation” (EEA)—that roughly corresponds to the environment in which humans were living 10,000 years ago, i.e., small groups of weakly genetically related individuals competing for scarce resources.

2) Morality is a “technology” that has evolved in this context to solve coordination and cooperation failures.

3) The distinctive traits of human morality that have evolved have been selected according to their fitness value for individuals and, eventually, for groups of individuals.

4) Because of the characteristics of the EEA, the traits of human morality that have evolved have mostly led to “exclusivist” moralities, i.e., moral systems that are organized according to an inner/outer group distinction.

5) These traits are “hard-wired.”

6) As a result, inclusivist moralities are necessarily “artificially engineered” and are unsustainable over the long run. Attempts to implement social practices and institutions based on inclusivist moralities will fail and are likely to have adverse consequences.

As we go from tenet 1 to tenet 6, we slide from solid factual claims to more hazardous, at least implicitly normative, conjectures. Tenets 1 and 2 are widely accepted nowadays. Tenet 3 is already far more contentious, if only because the coevolution between genes and culture may favor the selection of phenotypic traits that are not fitness maximizing—the obvious example is the demography of wealthy countries, which is largely driven by cultural factors. Tenets 4, 5, and 6 are doubtful. In their book, The Evolution of Morality, Buchanan and Powell convincingly argue that while the EEA may indeed have largely favored the evolution of traits favoring exclusive moralities, traits more friendly to inclusive moralities may have evolved thanks to different evolutionary mechanisms. The scientific state of the art suggests that humans have evolved a high level of cognitive plasticity that allows them to “switch” from one form of morality to another depending on environmental cues. It is true that human moralities have often been organized along the inner/outer group distinction, as suggested by the large evidence of the pervasiveness of inter-group conflicts. But this is by no means an evolutionary necessity (tenet 5 is false). More inclusive moralities are also sustainable, provided that the conditions are appropriate (tenet 6 is false).

The main point of contention between evoconservatives and “evoprogressives” is about the actual degree of cognitive plasticity, something that can be empirically assessed. Wade does mention that human cognitive plasticity somehow releases the constraints on politics. He also discusses cases where human nature has been successfully changed by politics, e.g., the quasi-universalization of monogamy. However, we may want to go further by investigating more specifically under which conditions politics can successfully remove or reshape its own constraints. Buchanan and Powell mainly emphasize the central role of economic conditions. They characterize inclusivist morality as a “luxury good.” The idea is that the kind of cultural innovations that favor inclusivist morality, but also other forms of “moral progress” (e.g., better compliance with existing moral norms, better moral motivations), are more likely to happen and to disseminate if socioeconomic conditions are highly favorable. This is relatively intuitive. The harsher the socioeconomic conditions, the more people have difficulties finding the means to maintain a minimal level of well-being. This increases competition for resources between individuals and between groups. In turn, this makes individuals’ environments less safe. There is evidence that more inclusive values that extend morality beyond family, clan, or kinship are more likely to take root in societies where individuals’ concerns for security are lessened. Inclusivist morality is a luxury good in the sense that individuals are inclined to endorse its constitutive values only when they feel safe and have their basic needs satisfied. Insofar as politics has a direct influence on socioeconomic conditions, that means that it also has partial control over some of the elements that constrain it. True, it may be almost impossible to politically manufacture a luxury good such as inclusivist morality, and attempts to do so may lead to spectacular failures.

Let me finish by highlighting two lessons from this discussion. The first is that what we know about “human nature” and its naturalistic roots is itself limited and subject to further revisions. It is crucial that politics is analyzed and practiced with an adequate knowledge of the underlying constraints. But the realist perspective also urges us not to idealize this knowledge. Arguments from evolution always run the risk of essentializing features of the natural and social world and of creating a false sense of immutability and certainty. This risk must be weighed in the political design endeavor. In the past, it materialized in false claims about the inferiority of certain “races” and the related justification of unequal political treatment. We do not know to what extent our cognition is plastic, and political claims must account for this uncertainty. As Raymond Aron wrote, “[i]f tolerance is the daughter of doubt, we should teach people to doubt models and utopias, and to reject prophets of salvation and disasters. We should wish for the coming of skeptics if they are to shut down fanaticism.”[4] This applies to all political claims, including those about the naturalistic origins of politics. Otherwise, politics turns into a secular religion, where nature is substituted for God.

The second lesson is that, while politics is a necessary evil, a good heuristic is to keep its stakes as low as possible. The more politics touches existential aspects of our lives, the more we may expect disagreement and conflicts. This is an argument to make politics more polycentric and, when not possible, to limit political power with political counter-power. Of course, if people tend to be so passionate about political matters, it’s precisely because politics is existential. What we want to avoid, however, is subjugating individuals to grand schemes that ignore their interests and values. Politics should not coerce people in the name of progressive fantasies, nor in the name of an elusive human nature.

[1] Nicholas Wade, The Origin of Politics: How Evolution and Ideology Shape the Fate of Nations – Social Disintegration, Birth Rates, and the Path to Extinction (Harper, 2025).

[2] Ibid., p. 85.

[3] Allen Buchanan and Russell Powell, The Evolution of Moral Progress: A Biocultural Theory (Oxford University Press, 2018). In what follows, I largely use the material from an old essay of mine published on this newsletter.

[4] Raymond Aron, L’opium des intellectuels (Fayard/Pluriel, 1955 [2010]), I translate.

Such a thoughtful take on evoconservatism and the limits of evolutionary arguments in political design. I particualrly appreciate your point that cognitive plasticity is itself uncertain, and using nature as a substitute for ideology can become just another form of dogmatism. The luxury good framing of inclusive morality is brilliantly insightful. Having wrestled with these questions in policy contexts myself, the balance you strike between realism and humility about what we actualy know feels exactly right.

thank you for this piece, cyril