Very short summary: This essay is a critical discussion of a recent FT op-ed by the economist Oren Cass arguing that free market and free trade are mutually exclusive. I argue that Cass’s “free market nationalism” is ultimately self-contradictory on philosophical, political, and economic grounds.

If you are a subscriber, don’t hesitate to answer to this reader survey to help me improve the content produced on this newsletter. It will not more than 3 minutes. Thank you!

Almost unanimous criticism from economists has met Trump’s tariff policies. That may explain why he, at least temporarily, stepped back from the most eccentric aspects of his protectionist agenda. The economist Oren Cass is among the few dissenting economic voices that have found some merit in this agenda. A couple of weeks ago, Cass published an op-ed in the Financial Times in which he developed an original argument in favor of Trump’s tariff policies. I have not seen this argument discussed much since then, so I would like to comment on it in this piece.

I would characterize Cass’s argument as a case for “free market nationalism.” Indeed, Cass claims that in our modern world, free markets and free trade cannot be realized at the same time; it’s either/or. In essence, that’s because the current globalized economy is not an interconnected network of free market economies or, even better, a single free market economy where economic borders have been abolished. It rather looks like an arena where nations compete by subsidizing their economic champions to gain global market shares. The critique of Trump’s tariffs is based on the misconception that free markets and free trade go together:

The error contained in this critique is the same one that free-traders have been making for a generation: imagining a global economy that operates like the friendly free market on the economist’s blackboard in which competitors sharpen one another and capital flows to its best use. Productivity rises, prices fall, everyone flourishes.

In the real world, by contrast, the global marketplace is dominated by government-built national champions. Capital flows towards the biggest subsidies and the most exploitable labour. Productivity falls, in the US anyway, where the typical factory requires more labour than a decade ago to produce the same output.

Cass suggests that we should view the tariff policies as the “bet” that it’s better to institutionalize a free market economy at the national level rather than sticking to free trade in a context where state interventions promoting national champions rig economic competition. One reason he thinks this bet might be won is that tariffs will encourage producers to (re)locate their activities in the U.S., an argument we have already heard from the Trump administration. The point is not to turn the U.S. economy into an autarky. In Cass’s ideal world, the tariffs will be just enough to close the trade deficit and leave the benefits that come from a free internal market intact. The bet rests on the fact that the U.S. economy is big and the losses due to an unavoidable reduction of exports will be more than compensated by the fact that U.S. demand will be more easily accessible for companies located in the country. In short, instead of producing and exporting goods, U.S.-based companies will sell to the national economy, a prospect so appealing that more companies will want to locate in the U.S.

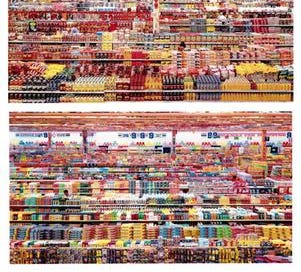

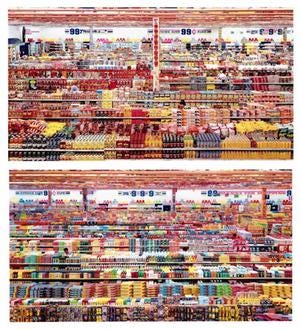

“99 Cent II Diptychon,” Andreas Gursky (2001)

The argument is superficially compelling, but it rests on shaky foundations. Let’s start with some empirical evidence. The idea that tariffs will encourage producers to locate their activity in the U.S. is theoretically plausible. Indeed, past experiences suggest that this may happen at the margins. However, the same experiences indicate that this effect is unlikely to compensate for the far more important harm that will be inflicted on U.S. consumers. Recent studies of the case of U.S. 2018 tariffs on washing machines indicate that the “relocation effects” of tariffs that apply to all foreign producers, while real, are weak and impose a significant cost on consumers due to higher prices. This cost is even more important once retaliatory tariffs imposed by other economies are accounted for. Now, we lack contemporary examples of the kind of massive tariff policies that Trump envisioned. One may argue that, when tariffs apply to all goods and all countries (though not uniformly), the relocation effects will be bigger. There is no obvious theoretical reason why we should expect this to be true, and this is, anyway, highly speculative.

Cass’s argument raises a more fundamental objection. The traditional considerations in favor of free markets apply, in principle, as much within and across borders. While comparative advantages are most often discussed with respect to international trade, the underlying logic works as well, if not better, in interpersonal trade. Similarly, the relationship between division of labor and the size of markets is completely independent of the existence of national economies. The case for free trade is, originally at least, nothing but the generalization of the case for free markets. Voluntary exchanges are good because they facilitate and encourage specialization, which in turn reduces production and the prices of goods, expanding the “opportunity set” of individuals in a context where we want to let them decide what to choose from this set. Whether people live in the same territory or not, speak the same language or not, or share the same cultural mores or not, all this is irrelevant.

Actually, during the 20th century, the case for free trade (including the free movement of capital assets) has capitalized on another argument, which is that free trade provides a safeguard against temptations to impede the operations of free markets at the national level. As the intellectual historian Quinn Slobodian argues in his book The Globalists, the institutionalization of free trade has been conceived by the members of the “Geneva School” (Mises, Hayek, Röpke) as a way to ensure that states would not interfere too much with the operation of market processes.[1] The best way to protect free markets is to expand them beyond borders, so that they are beyond the control of state authorities.

Finally, the ethical argument that free markets realize in the economic domain the fundamental value of freedom and give individuals the possibility to pursue the values and ends of their choice also extends beyond national borders. If it is good to let individuals be free to choose what to consume and, more generally, how to pursue the ends that they value the most, why would you argue that this is true only when they buy goods produced on the national territory?

Therefore, the disentanglement of free trade and free markets rests on the introduction of an additional pair of considerations, one normative and the other positive. The normative consideration is the claim that the welfare and freedom of some people matters more than those of other persons. The positive consideration is that artificially raising the price of foreign goods will improve these people’s welfare and freedom over the long run. Regarding the latter, as I point out above, we have reason to doubt this is the case, even in the imperfect world of not totally free market economies that Cass describes in his text. Even if that were the case, the former consideration faces the objection of arbitrariness. Acknowledging that the effects of tariff policies will not be uniform across the American population, what does justify the choice of the national economy as a reference point? The “American national economy” is neither less nor more real than the economy of Texas or the population constituted by middle-aged, educated white male Americans.

Cass’s opposition between free trade and free markets is artificial. It postulates that we can have free markets without free trade. This is hardly imaginable in the contemporary globalized economy, where supply chains ignore national borders. Moreover, from its early conception, the idea of extending freedom to economic activities of producing, selling, and buying goods was not meant to apply within the borders of a national economy. Free trade does not “undermine” the free market, as Cass writes. The philosophy, politics, and economy of the free market imply free trade. The philosophy of the free market ignores national borders, and the choice of the nation as a reference point is totally arbitrary. The politics of the free market has historically relied on free trade as a check against state power. Finally, the underlying economic logic that accounts for the benefits (and also the drawbacks) of the free market also applies to international trade.

There is therefore something paradoxical, both empirically and philosophically, in contending that, in a world where free markets are impeded by state policies that promote “national champions” (a point we might eventually grant to Cass), the spirit of the free market can be recovered by limiting trade based on nationalistic considerations. This paradox is not merely apparent, and it makes “free market nationalism” a self-contradicting idea.

[1] Quinn Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Harvard University Press, 2018).