[Note: it may happen that the article doesn’t appear in full length in your mailbox because of the photos. In this case, you can read it full-length on the website]

My wife and I are back from a 7-day trip in New York City. That was my second time in NYC and I have even more enjoyed the city than the first time. We of course went to traditional tourist places (the Statue of Liberty, the Museum of Natural History, the MOMA, and the Empire State Building), but also attended a Broadway play and the Roquettes Christmas Show, and visited the Morgan Library. There were also purely “intellectual” activities, as we went for a Reason conversation where the historian Jennifer Burns was talking about her recent biography of Milton Friedman. And, of course, we went to several bookstores (Rizzoli, Strand, Barnes and Nobles, Argosy, McNally Jackson). Unsurprisingly, I returned with several books in my luggage. Among them was an old copy of Karl Popper’s The Poverty of Historicism, a book that I had never read until now. I have read it since, and this gives me an excuse for today’s post about historicism.

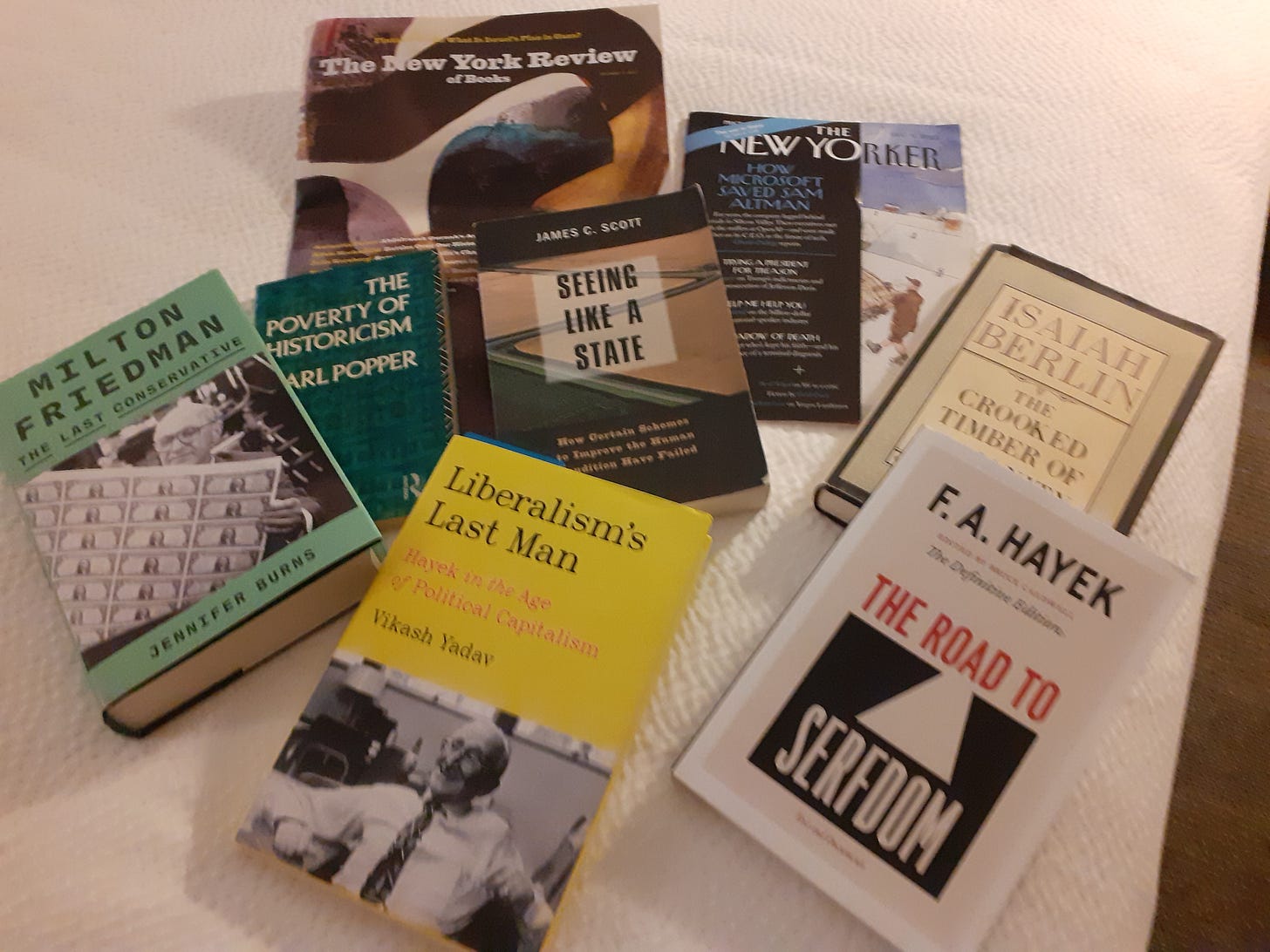

What I brought from NYC!

…………………………………………..

To say that historicism has a bad press is an understatement. More than having a bad press, it is actually a largely forgotten thesis, and Popper’s book – along with its companion, The Open Society and Its Enemies – bears some responsibility for this.[1] The context in which Popper was writing his critique is well-known. The world was in the midst of its most destructive global war, a war essentially caused by the rise of totalitarian ideologies and regimes. Popper, along with several other intellectuals of the time (e.g., Hayek and, with maybe some caveats, Aron) saw a link between these ideologies and regimes and then fashionable ideas mostly originating in German philosophy and social sciences. Historicism is a catchword that has been often used to capture these ideas, most of the time not in a very rigorous way. Anyway, that Popper links historicism to totalitarianism is pretty much clear even before the beginning book, which is dedicated to the “memory of the countless men, women and children of all creeds or nations or races who fell victims to the fascist and communist belief in Inexorable Laws of Historical Destiny.” My interest here is not to assess this putative connection – that Popper actually argues for in The Open Society more than in The Poverty – but to reflect on the intellectual standing of historicism in light of critiques like Popper’s.

Reading in Rizzoli

Characterizing historicism is not a straightforward task. Popper defines it as “an approach to the social sciences which assumes that historical prediction is their principal aim, and which assumes that this aim is attainable by discovering the ‘rhythms’ or the ‘patterns,’ the ‘laws’ or the ‘trends’ that underlie the evolution of history.”[2] Thus defined, historicism appears as a methodological thesis that is derived from positivism – for its emphasis on predictions – but with an insistence on the specificity of history as an object of study. Not everyone finds this definition relevant, though. Francis Fukuyama for instance disparages it, and instead argues that the defining characteristic of historicism is its emphasis on the relativity of truth with respect to historical periods.[3]

In my opinion, none of these definitions is fully satisfactory. I will indulge myself in referring to my PhD work on what I then called “historical institutionalism” and where I was trying to characterize the epistemological basis of various historicist and institutionalist accounts of capitalism.[4] Based on this, I would suggest that historicism is best viewed as an epistemological thesis about the nature of historical knowledge with methodological and, eventually, moral/political implications. More specifically, historicism can be characterized as a specific view of the relationship between history and (social) theory. On the one hand, historicists emphasize the historical dimension of the very activity through which theories of society are elaborated. Let’s call that the historicization of theory. On the other hand, they argue that the activity of theorization is aimed at uncovering the mechanisms, trends, or eventually laws that account for the way (local or global) history unfolds. Let’s call that the theorization of history

Santa and I had a nice talk at the top of the Empire State Building

This is a very broad definition that encompasses a vast array of philosophical and social science types of analysis. It is nonetheless precise enough for strictly delimitating a thesis with specific methodological and moral implications. At first sight, the two constitutive principles of historicism may seem to be inconsistent. And up to some point, they indeed are. It is indeed not difficult to see that their strict applications can lead to contradictions. The historicization of theory is related to Fukuyama’s emphasis on the relativity of truth. For a historicist, a proposition P may be true in some historical context H but false in some other context H’. For instance, as German historicist economists of the 19th century forcefully argued, the principle (some would say “law”) of comparative advantage applies to early 19th century England but not to mid-19th century Germany because the latter, contrary to the former, is not yet industrially developed. As such, there is nothing uncontroversial in this. As Popper clearly shows, the conditionality of the truth-value of a scientific proposition is also to be found in the natural sciences – e.g., the boiling point of water is conditional on atmospheric pressure. The difference however is that while a scientific law always specifies the “initial conditions” where a particular causal statement applies, historicists deny that any law or general proposition can be formulated with respect to human societies embedded in historical time. In the most extreme versions, this impossibility is located in the specificity of the “spirit” or “culture” of each particular people that is unfit for any theoretical-nomological generalization. If this is granted, however, then it seems that the second branch of the fork – the theorization of history – is vain to pursue. Historicists circumvent the difficulty by arguing that “laws of historical development,” of a different nature than laws natural sciences are after, nonetheless exist. These laws do not apply to specific historical societies but govern the general movement of history through which societies pass through different “stages.” From Comte to Marx, passing through Roscher and Schmoller, historicist philosophy and social science abound in such theories of the laws of history.

A glimpse at the amazing architecture of the Guggenheim Museum

Viewed from the lens of 21st-century empirical social sciences and analytical philosophy, historicism may seem completely crazy. The “historicization of theory” seems to open the door to all kinds of unacceptable relativism backed by a vast range of unscientific prejudices about individuals’ gender, race, religion, and other identity markers.[5] As for the idea of the existence of “scientific laws of historical development” that can be discovered, it is based on a mistaken understanding of the logic of science that Popper’s critique completely demolishes. This is, as Popper says, the “central mistake of historicism.”[6] It consists of mistaking trends (that, by definition, depend on a set of initial conditions) for laws, the latter being necessarily invariant because their statements include the set of initial conditions to which they apply. The problem is that as initial conditions unexpectedly change as time passes by, a trend cannot be “absolute.” There is no law of historical development, because statements about history are singular, i.e., they are always dependent on initial conditions. In the preface of the 1957 edition of The Poverty, Popper mentions his “refutation of historicism” published elsewhere and that strengthens this critique. Basically, among the “initial conditions” on which statements about history depend figure the state of human knowledge. As the growth of human knowledge cannot be logically predicted (if you know now what you will know only in the future, that means that it is current, not future, knowledge), you cannot predict the future course of human history. Thus, “theoretical history” is impossible.

Go Knicks, go! (If you look attentively, you can see Michael J. Fox and Kevin Bacon, opposite first row, next to the scoring table!)

So, is there definitely nothing of value in historicism? I think it would be too radical to accept this conclusion. As a first argument in support of historicism, I would point out that somewhat paradoxically, it can be a good antidote against unjustified beliefs in moral and social progress that can back moral and political views. One of the reasons why Isaiah Berlin – himself a forceful critic of the moral implications of the idea of historical inevitability that many historicists endorse[7] – got interested in romanticism (itself a branch of historicism) is precisely because provided a warning against the Enlightenment pretense to identify a unique core of overarching values based on which human progress could be asserted. Indeed, as John Gray has convincingly argued, liberal thought has not been immune to the idea that there were historical laws of human progress and has sometimes developed its own philosophy of history.[8] Berlin’s engagement with romanticism is related to his defense of value pluralism. The plurality and incommensurability of values defeat any attempt at identifying a trend of moral progress. Value pluralism points out that any statement about the moral status of a behavior, an institution, or society is relative to a particular form of life and that the range for general propositions about values is fairly restricted. While it may put into service in some cases of unacceptable forms of relativism, it is also a strong support for the defense of freedom.

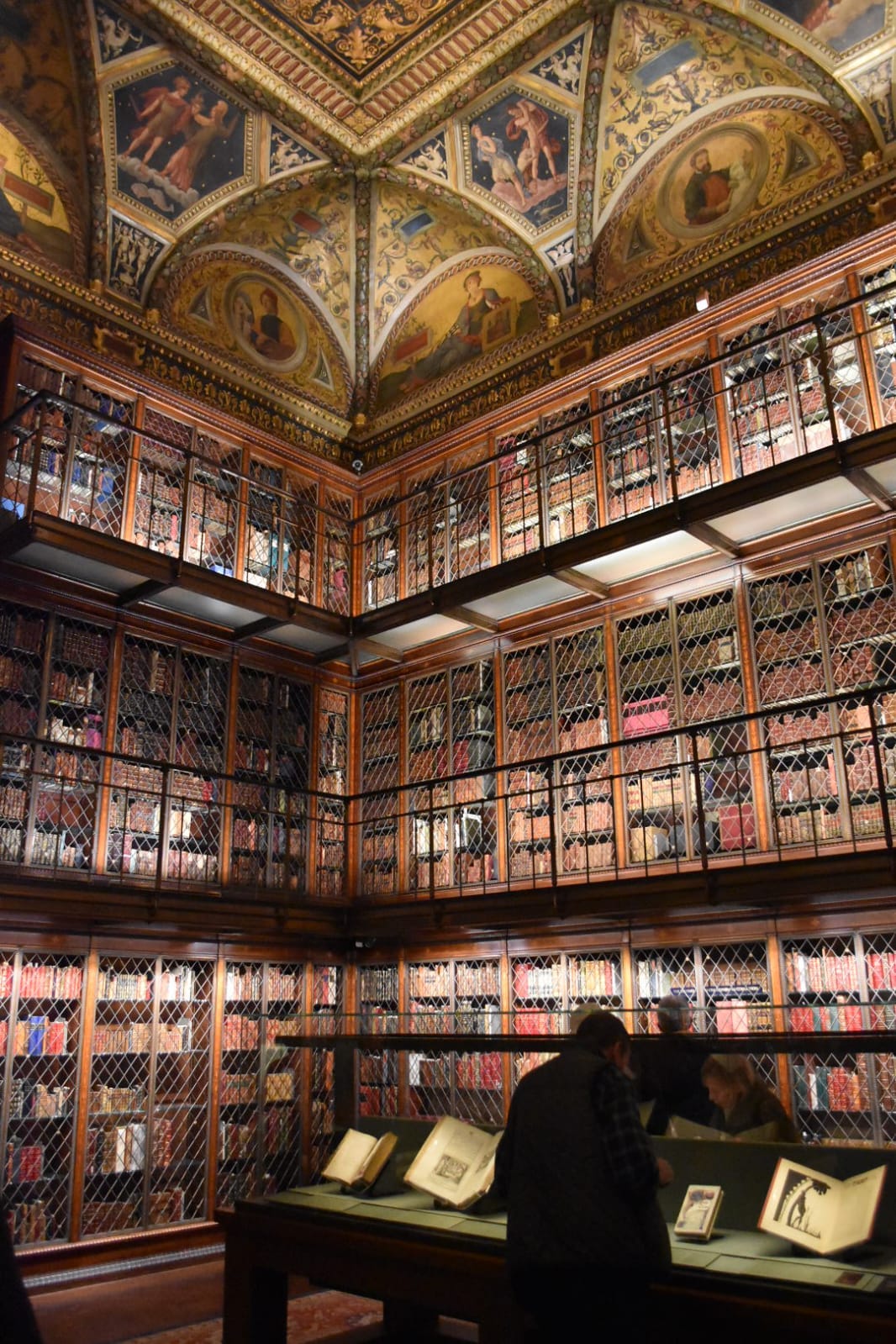

The Morgan Library is beautiful

There are obvious moral dangers that go along with the idea of theorizing and predicting history. Berlin notices that a belief in the inevitability of history necessarily weakens the value of individual responsibility.[9] Popper argues that historicism is naturally associated with “holism” and “utopianism.” Against the idea that we should cautiously experiment with society through “piecemeal engineering,” historicism licenses us to attempt holistic social changes that can easily lend themselves to totalitarianism. On the other hand, theorizing about history is unavoidably part and parcel of philosophy and social sciences. Historicists were wrong that, except for laws of historical development, no general statement about society can be made. Because of this, they exaggerated the differences between natural and social sciences. But they were right that, in an important sense, the historical nature of social events confers to values a more prominent role than in natural sciences. Historical is a complex web of an infinite number of single social events. The practice of social sciences necessarily calls for what Max Weber calls “value-relevance,” i.e., the intentional identification of relevant events based on value judgments. Whatever the level at which you are theorizing and doing empirical research, values justify your methodological and theoretical choices, as well as the scope of your analysis.

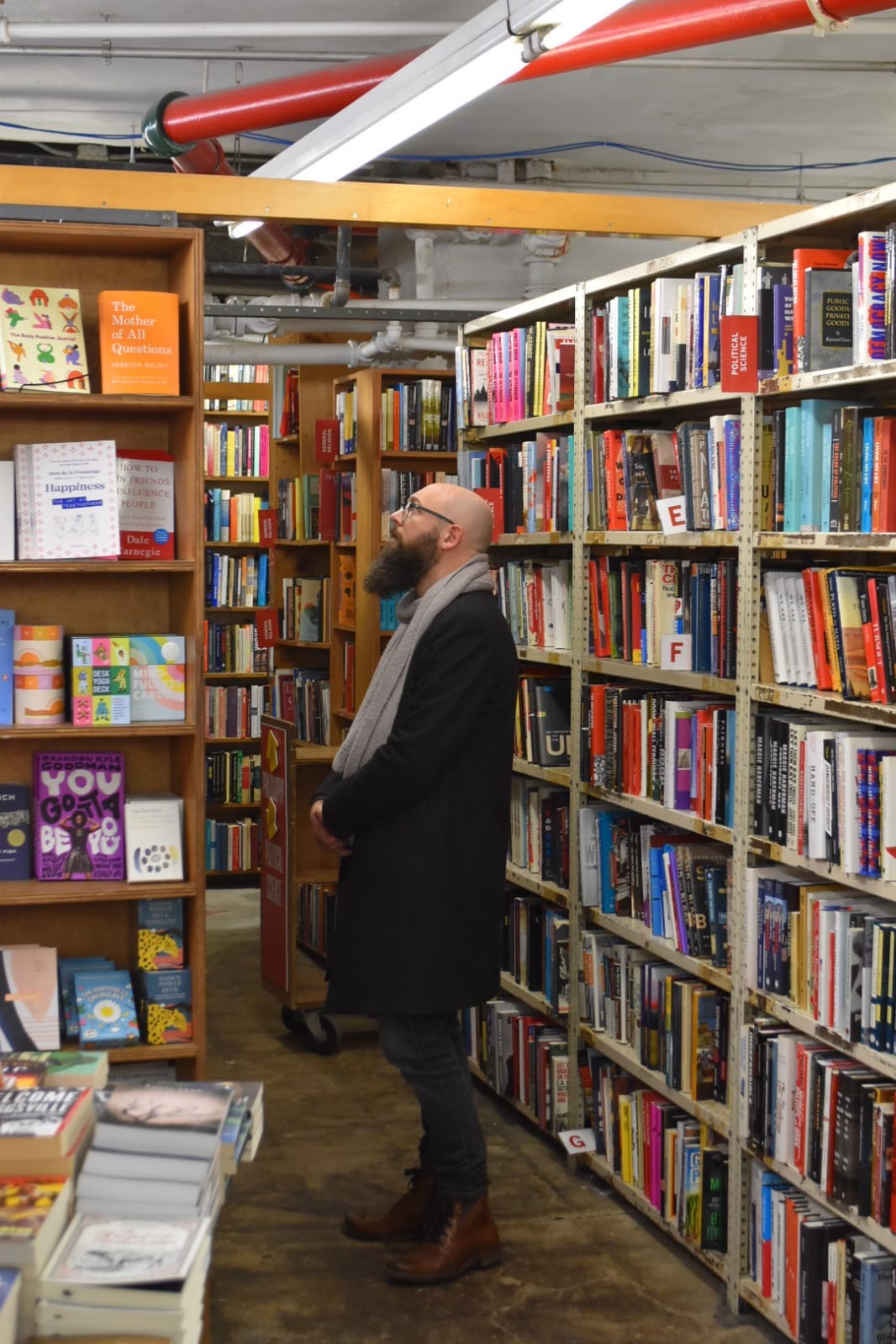

Overwhelmed by books at Strand!

This is important because, though few if any social scientists nowadays would call themselves “historicists,” the interest in theorizing about history has not disappeared. There are several significant examples of distinguished scholars who still think that it makes sense to provide theories accounting for global historical trends, either past or future. There is of course Fukuyama’s end of history thesis,[10] but also Acemoglu and Robinson’s account of the transition from dictatorship to democracy,[11] or Peter Turchin’s attempt at founding a “cliodynamics.”[12] Compared to genuine historicists, these scholars do not commit the mistake of thinking that there are “historical laws.” What they rather identify are trends based on specific mechanisms that can be modeled and empirically assessed. The identification of a mechanism M at the same time explains some specific social event (or the connection between two such events) and gives reason to believe that similar events will repeat in the future or that a particular trend will persist. But it is also perfectly compatible with the acknowledgment of the indeterminacy of history, the role of individual responsibility, and the awareness that this theorizing does not license any bold proposal about social change.

Interestingly, and this is sometimes forgotten, Popper does not say the contrary. Contemporary historical theorizations largely proceed along the “situational logic” that he sketches. At times, Popper does indeed sound very Weberian, as when he acknowledges that “there can no history without a point of view” and that studying history requires “to introduce a preconceived selective point of view into one’s history; that is, to write that history which interests us.”[13] To do that, however, is nothing but proceeding to the “historicization of theory” that characterizes the historicist epistemology. As far as such historicization proceeds based on value judgments that are themselves constitutive of a broader philosophical framework, all theoretical accounts of (both global and local) history are philosophies of history in their own right. Contemporary theoretical studies of historical trends say a lot about our societies, both because they try to explain their dynamics, but also because the very shape they take reflects entrenched value judgments.

Historicism may be a doctrine of the past but in its moderate and self-conscious form, it nonetheless continues to inform contemporary philosophy and social sciences. History is at the same time an object to be studied by philosophy and social sciences but also provides the context in which they can develop.

[1] Karl Popper, The Poverty of Historicism, 2nd edition (London: Routledge, 1944 [1957]). Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, 5e édition (London: Routledge, 1944 [2011]).

[2] Popper, The Poverty of Historicism, p. 3.

[3] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (Penguin Books, Limited, 1992 [2012]).

[4] Cyril Hédoin, L’Institutionnalisme historique (Paris: CLASSIQ GARNIER, 2014).

[5] What we call “identity politics,” which itself relies on an “identity epistemology” is definitely in line with historicism. When you argue that the truth value of propositions differs depending on which categories of persons they apply to, and that only the persons belonging to this category can assert it, you are pushing for an extreme version of the historicization of theory thesis.

[6] Popper, The Poverty of Historicism, p. 128.

[7] See in particular Berlin’s essay Historical Inevitability (London: Geoffrey Cumberlege, Oxford University, 1954).

[8] John Gray, Two Faces of Liberalism (Oxford: The New Press, 2002).

[9] Berlin, Historical Inevitability.

[10] Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man.

[11] Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

[12] Peter Turchin, Historical Dynamics: Why States Rise and Fall (Princeton, N.J. Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2003).

[13] Popper, The Poverty of Historicism, p. 150.

Interesting. Do Western ideas of history come from a long line of freedom values? First the Classical , then the post classical that realizes universal security and freedom? The example of a boiling water is interesting: Modern China would be frozen water; while Africa would be boiling water. From our reference point. Liberalism and Republicanism then try and keep the water between those absolutes.

We draw on our consciousness to create the objects we desire in the present and future? Now, from technology, billions are engaging in that human action! Liberalism and Republicanism seem the best ideas or logic to have a chance of ending history: to restrain power and secure individual exceptionalism. Maybe not end history but burst it into fragments.