Political Disagreement Beyond Echo Chambers

On the Requirements of Intelligibility and Sincerity

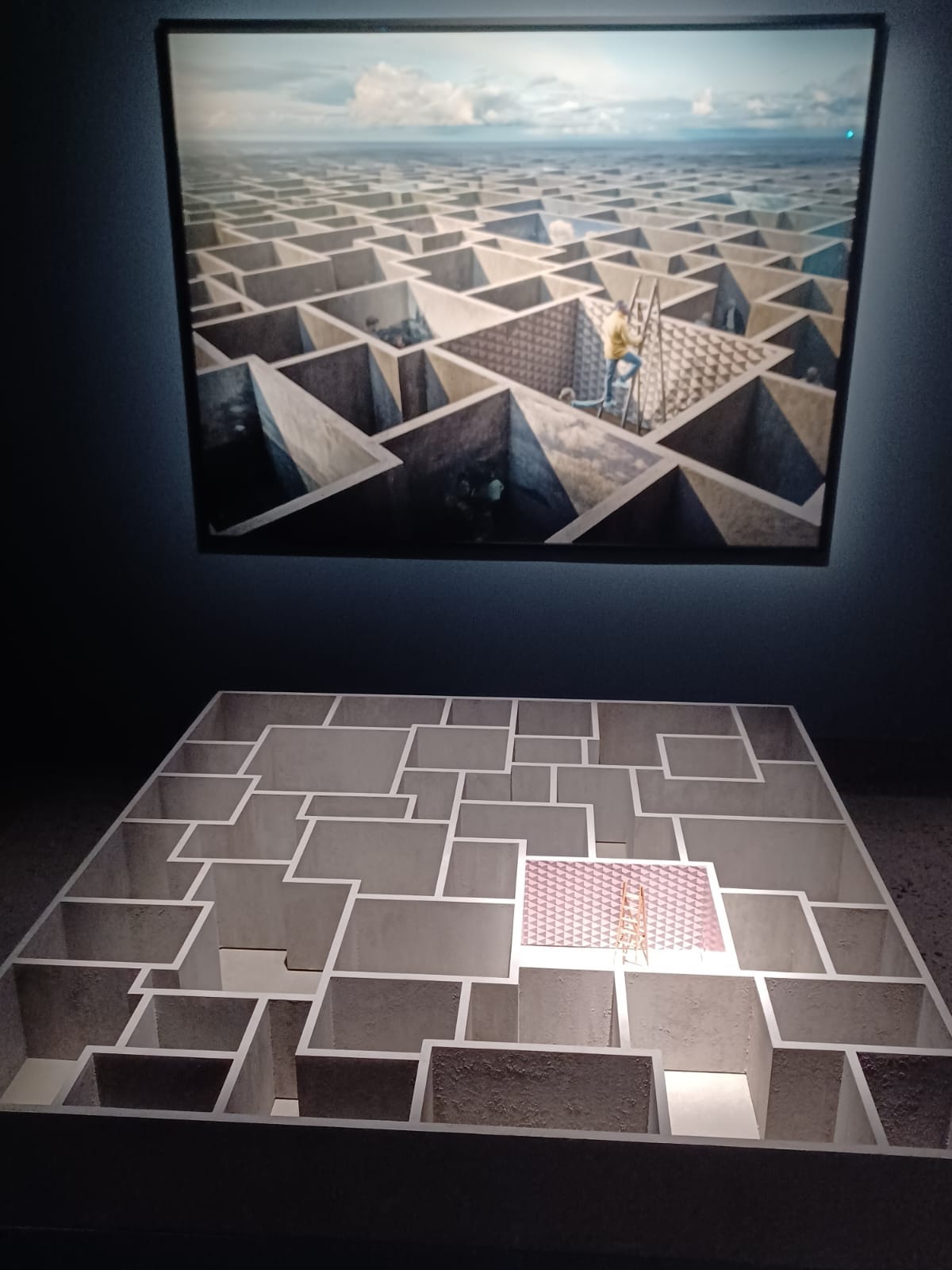

I’m back from a short trip to Oslo, Norway. Compared to other Scandinavian capitals like Stockholm and Helsinki (I’ve never been to Copenhagen, yet), I find Oslo more modern and “cold.” There is beauty in modernity of course, but it lacks the charm of Stockholm’s downtown. That said, the architecture of some buildings, especially the opera and the public library next to it, is absolutely stunning. Oslo is also where the Nobel Peace Prize is awarded. We’ve visited the dedicated museum – we found it a bit disappointing, especially when compared with Stockholm’s bigger Nobel Prize museum. Still, we went there also to see the exhibition of the surrealist Swedish photographer Erik Johansson, titled “The Echo Chamber.” I find Johansson’s work quite fascinating and though the exhibition is quite modest, it provides an interesting perspective on the problem associated with our difficulty in opening ourselves to views that contradict our perceptions, beliefs, and judgments. What follows is a short reflection on this and related subjects – accompanied with some photos from the trip.

Munch Museum

The exhibition reminded me of a recent essay by Dan Williams on “conspiracy theories of ignorance.” In this essay, Dan criticizes the doctrine that truth is manifest, in the sense that it is accessible and, once ascertained, is easily distinguished from falsehoods. Following Karl Popper, Dan notes that the doctrine of manifest truth easily lends itself to the idea that if people reject or ignore the truth, that must necessarily be because they intentionally do so, or because they are manipulated by some obscure forces in the background. Individuals who don’t accept the truth are either irrational or the victims of some conspiracy by some persons who have an interest in suppressing the truth.

Dan goes on to argue that something like the conspiracy theories of ignorance are at play in popular accounts of disinformation, i.e., the fact of providing false information to deceive and manipulate people. He offers a convincing rebuttal to these accounts that I’ll not repeat, but there is one point on which I would like to comment. Dan rightfully notes that by ascribing to those with whom we disagree the intention to deceive, or by assuming that these persons are manipulated, we undermine the very possibility of public discussion:

“Although a failure to detect and punish dishonesty can increase the amount of dishonesty, the tendency to classify people’s sincere views as dishonest tends to poison political discourse and exacerbate polarisation.”

This is a fundamental point that is unfortunately not enough acknowledged. To understand why, we need to look in more detail at what can account for the disagreement between two or more persons. At the bottom, disagreement is always about beliefs: beliefs about what to do, beliefs about what is true, beliefs about what is fair or good, and so on. In some cases – and this is what proponents of conspiracy theories of ignorance have in mind – the disagreement originates in the fact that persons just have different interests. That does not necessarily make it insincere, especially if the divergence of interests is transparent. But at least when fact-based issues or normative issues in which assessment demands some impartiality are at stake, we may prefer that judgments are not polluted by interests.

Oslo Opera House

People routinely disagree about facts and values. Contemporary accounts of echo chambers and the related concept of epistemic bubbles suggest that modern technology, e.g., the algorithms of social networks, creates polarization by locking in people in hermetic informational spaces. These spaces filter the information individuals are accessing according to predetermined and self-reinforcing patterns. There clearly is a grain of truth in these accounts – after all, it is highly unlikely that two persons who have access to two radically sets of information will agree on anything. On the other hand, they at the same time exaggerate and underestimate the problem they identify. They exaggerate the problem because (as Dan has argued many times on his blog) it appears that the informational spaces created by algorithms are not so hermetic after all. While the epistemic chambers do create some echo, most people do not stay in them, unless they willingly choose to do so. These accounts thus end up underestimating the issue because they falsely give the impression that, provided we could tear down the walls of the echo chambers (or make them capable of looking “above” the walls as in one of Johansson’s photographs - see below) created by algorithms, disagreement would largely disappear.

The mistake here is to assume that disagreement is mostly due to the fact that individuals do not share the same information. However, disagreement has deeper roots located in human psychology. The problem is not so much related to the availability of information than the way it is used. This can be traced back in part to the largely documented “cognitive biases” that affect the way we collect and treat information.[1] The term “biases” is however problematic because it tends to suggest that disagreement is due to irrationality. Even more fundamentally however, disagreement is explained by the fact that we don’t all share the same perspectives over the world. As the political philosopher Ryan Muldoon explains,[2]

“Perspectives are simply the filters that we use to view the world. This supposes that we do not take in the world “as it is,” but instead (consciously or unconsciously) choose to group certain features together, choose to ignore certain information while focusing on other information, and choose systems of representation and interpretation. Perspectives are thus mental schemata that embody those choices. Cultures will often share a great many perspectives.”

Thus conceptualized, perspectives are a conjunction of evaluative standards (i.e., values) with “a particular ontology to a class of situations.”[3] I’ve argued in an old post here that such “perspectival diversity” can make agreement impossible, even when individuals share the same information. The bottom line is that, if echo chambers and epistemic bubbles exist at all, they are tied to the fact that individuals cannot process information outside a given perspective.

On a boat trip!

It is possible, at least up to a point, to overcome perspectival disagreement. Since this is an essay that reflects my stay in Oslo, let me illustrate the point with my favorite painting from the most famous Norwegian painter, Edvard Munch:

The painting’s title is “Vampire.” Maybe because of that, I’ve always viewed this painting as figuring a woman biting a man’s neck, the woman’s long red hair evoking traces of blood. This is definitely a particular perspective on the painting. Now, there is at least a second plausible perspective that sees the woman comforting the man. As the original title of the painting (the one given by Munch) was “Love and Pain,” this may be the “correct” interpretation. Which interpretation is correct is beside the point, however. I just want to illustrate that, in some cases at least, people can discuss perspectives and, eventually, reach an agreement.

Admiring Munch’s Vampire

I see at least two necessary conditions for such an agreement to be possible. First, the reasons and values that each individual brings to the public discussion must be intelligible. There is no discussion possible if the interlocutors don’t understand each other. Even if they don’t agree initially, they must be able to make sense of the others’ beliefs regarding what justifies their views. Second, and this circles back to Dan’s post, individuals must ascribe to each other sincerity. Each individual must believe that others are sincerely asserting their views. There is no point discussing with someone you believe is trying to deceive or manipulate you or who is pursuing their interests in complete disregard to your own views – eventually, you may bargain with this person, not discuss.

The difficulty is that intelligibility and sincerity may be difficult to achieve in the context of perspectival diversity. By definition, it’s not always possible to share someone’s else perspective. You can eventually get used to others’ perspectives, and have some “theoretical” knowledge of it, but the more “practical” knowledge that is attached to it will remain definitely inaccessible. Consider for instance the difficulty for a man to really understand what it is for a woman to be harassed on a daily basis or for wealthy nationals to put themselves in the shoes of desperate migrants willing to risk their lives to escape their country. Fortunately, public discussion and an eventual agreement don’t require full-blown empathy and the complete adoption of others’ perspectives. What intelligibility requires is that we can make sense of other demands in light of what we understand about their perspectives.

In Ibsen’s apartment

Sincerity may even be more difficult to achieve, though. Sincerity demands that one’s claims and views are really based on one’s perspective. This is precisely what those who hold conspiracy theories of ignorance tend to deny. They tend to assume that if others disagree with them, that must be due to some hidden interests (in which case they are insincere) or to their irrationality (which undermines the intelligibility of their claims). Obviously, the problems of intelligibility and sincerity compound. The less you can make sense of others’ perceptions, the less you’re likely to attribute sincerity to their views. However, because intelligibility doesn’t mean transparency, you can still doubt someone’s sincerity even if you understand their perspective.

What we have here is a kind of adverse selection. Consider the twofold fact that (i) individuals are indeed sometimes insincere and (ii) that establishing someone’s else genuine insincerity is a good way to disqualify their claims and views. Even if everybody agrees that mutual ascription of sincerity is required for a productive public discussion and an eventual agreement, it is tempting to doubt others’ sincerity. This is even more so as there is a second-order problem: you may not want to ascribe sincerity to others if you think that they may not reciprocate.

The impressive mayor house

This is the kind of situation in which we are today. The core of the issue is not so much that there are echo chambers but that there is widespread distrust in each other’s willingness to make a sincere case for their views. When intelligibility and sincerity are secured, at least we can agree that we disagree. This very basic agreement sets the ground for institutional solutions, such as classical democratic voting procedures or jurisdictional rights of property and privacy, to adjudicate between competing views. Public justification does not entail full-fledged agreement and even less unanimity. What is required is that individuals understand each other enough and are somehow convinced of everybody’s goodwill to find acceptable compromises compared to a modus vivendi type of situation where nothing else than the balance of interests matters. Today, in many Western countries,[4] these requirements are no longer met. What is even more worrisome is that mutual distrust is self-fulfilling and self-reinforcing. Liberal politics is grounded on the possibility of a peaceful and reasonable disagreement. Once this possibility is jeopardized, what is left is a kind of Hobbesian war that cannot be easily exited.

[1] With respect to politics, see for instance Christopher H. Achen and Larry M. Bartels, Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

[2] Ryan Muldoon, Social Contract Theory for a Diverse World: Beyond Tolerance (Routledge, 2016), p. 48.

[3] Ibid., p. 50.

[4] And also maybe on the international stage. Vance’s Munich speech exemplifies the case where it is not easy to distinguish between views that sincerely follow from a given perception and more basic national interests weighing in an international bargain. I leave this for a future post.

I have mixed feelings about this. I think it's very well argued and I read Dan Williams' linked piece which I thought was right to include the specific examples when people really are being insincere.

I also think that on an individual level, the best way to change minds is to first build relationships with people. Only once you have a certain level of trust can you have productive disagreements that may change deeply held beliefs.

On the other hand, at least in the U.S., the context I know most about. My understanding is that the political right (I'm talking power brokers/politicians) has been insincere as a political strategy for at least decades. The Powell Memo and the Southern Strategy are two perfect examples of this and I think both efforts largely succeeded in completely changing American society and politics while knowingly claiming to want different end goals than what they are actively pursuing and achieving. I noted on another post of yours that the book Dark Money details how Koch-funded political consultants recognized how unpopular their ideas were and did focus groups to workshop insincere ways of presenting their ideas so they would get the most traction, and explicitly recognized this in a room of wealthy donors.

I think people also rightly criticize Democrat politicians/leaders for being insincere as they co-opt the language of progressive movements, but continue the same neoliberal reforms the right was pushing for that have the opposite effect.

All this to say, I think these pieces hold broadly true for individuals, and it's important to understand how we can approach others with a goal toward understanding others. However, I think the problem of insincerity is much, much bigger at the top of the power structure than is hinted at here and I think that besides the actual I sincerity, the next biggest issue is the ease with which we assign insincere motives to someone following an insincere leader.

My interpretation suggests one fix could be a focus on small-scale/local democracy and organizing and reduce the power of those at the top to polarize the nation.

"Public justification does not entail full-fledged agreement and even less unanimity. What is required is that individuals understand each other enough and are somehow convinced of everybody’s goodwill to find acceptable compromises compared to a modus vivendi type of situation where nothing else than the balance of interests matters"

I am not persuaded that the world outside that populated by educated people imbued with at least basic post Enlightenment rationalism has ever met that requirement.

This fact (!) has just previously been hidden by social political complexities that are now being leveled to reveal the way of interests you fear.

Scales are starting to fall from eyes. The zombie apocalypse is upon us.