Preliminary note: This essay is the last one before my summer break. The newsletter will not stop completely, though. See at the end of the post for more information.

A couple of weeks ago, Eric Schliesser published an essay on Gerald Gaus’s criticism of Isaiah Berlin’s account of value pluralism. Eric is commenting on the chapter Gaus dedicated to Berlin and value pluralism in Contemporary Theories of Liberalism.[1] As it happens, Gaus and Berlin are two of my favorite philosophers. Since I read the book a long time ago, that gave me the urge to reread the chapter. Eric does a fairly good job depicting Gaus’s view. In what comes below, I add some more general remarks suggesting that Gaus’s critical take on value pluralism is a more general feature of public reason liberalism’s uneasiness with what I would call the irrationality of politics.

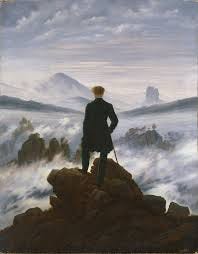

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (Caspar David Friedrich, 1818)

First, to expand on Eric’s essay a bit, Gaus distinguishes between several interpretations of value pluralism, all of which can be plausibly attributed to Berlin. He focuses however only on the two more interesting, the “incompleteness” interpretation and the “overcompleteness” interpretation. The former is the most natural, not only because it is the one attributed to Berlin by influential philosophers such as John Gray[2] and Joseph Raz,[3] but also because this is the most straightforward way to formally characterize value pluralism within the formal apparatus of rational choice theory. Under this interpretation, value pluralism is related to the incommensurability either of choice options or of the underlying evaluating criteria to rank the choice options. Consider two options A and B. Incommensurability results from the fact that we neither have A better than B (A > B), B better than A (B > A), nor A as good as B (A = B). Formally, that means that A and B cannot be ranked against each other. A corollary (emphasized notably by Raz) is that you can have a failure of transitivity. Consider a third option C such that A > C. If we had A = B, then transitivity would imply that B > C. But if A and B cannot be compared, this doesn’t have to be the case; we can have B = C or even C > B without any contradiction. Incommensurability of choice options will often be caused by the incommensurability of the underlying evaluation criteria. Let's say you have two such criteria c1 and c2 and that A is better than B according to c1 and B better than A according to c2. Now, to say that c1 and c2 are incommensurable means that if they conflict in their ordering of A and B, then you cannot order A and B because there is no possibility to define a trade-off between c1 and c2.

The overcompleteness interpretation characterizes value pluralism as a situation of evaluative inconsistency where we have A > B and B > A at the same time. In this interpretation, there is at least one evaluative criterion that gives a reason to choose A over B and one criterion that gives a reason to choose B over A. Because there is no additional reason to give more value to one criterion over another, what we have is a genuine conflict. These two interpretations are very different, both from the perspective of decision theory and with respect to the implications of value pluralism. The incompleteness interpretation is mostly unproblematic in terms of rational choice analysis but the overcompletness interpretation is rejected by all plausible axioms of rational choice. Indeed, as Gaus recognizes, “overcompleteness cannot be a feature of a rational system of values.”[4] Even more fundamentally, the incompleteness interpretation is amenable to a “derivative” understanding where incommensurability is reduced to more fundamental causes such as the vagueness of the evaluation criteria and the uncertainty surrounding the social and moral world. To use Amartya Sen’s categories, incompleteness would only be “tentative” rather than “assertive.”[5] That implies that with more information and deeper reflections on the articulation between the evaluation criteria, it is possible in principle to rationally overcome the incompleteness.

Gaus’s critique leads therefore to a rejection of the idea of value pluralism at least it has been characterized by Berlin and his followers. On the incompleteness interpretation, pluralism is not a fundamental (i.e., ontological) fact of the world, but rather an epistemic feature due to our lack of knowledge and information. The kind of incommensurability underlying value pluralism is not a sign of irrationality (it is more often than not rational to not be perfectly informed) but it can in principle be eliminated or at least significantly reduced. On the overcompleteness interpretation, value pluralism is nothing but the manifestation of irrationality. One way or another, value pluralism cannot be a long-standing feature of our coherent social and moral systems.

In his essay, Eric rightly observes that even if we agree with Gaus that pluralism at the individual level is either tentative or irrational, that does not say anything about its status at the social level. More specifically referring to the overcompleteness interpretation, he writes:

“But when we move up a level from individual agents to social decision-making what Gaus calls ‘overcompleteness’ may be the effect of the existence of polarization or multiple social tribes/factions in society. And here a social decision is potentially not at all informative or constitutive, but better described as the imposition by the state or society of the most influential faction — maybe the majority — on the minority. And, in the politically salient context of tragic choices, it may well undermine the existence of the purported social agent, or lead to civil war. Think of the decision to elevate one system of values — or religion — to state monopoly.”

And he adds:

“Yet, another way of looking at Gaus’ argument is this: definitional consistency comes at the price of not even trying to accommodate the rivalrous nature of political life where the rivalry is the product of systemic overcompleteness. After all, lurking in Berlin’s position is the Weberian insight (that we also find in Hume and, especially, Adam Smith) that we should not press on the rationality or reasonableness of social decision-making too hard.”

Those are very important remarks. You can interpret the most famous results of social choice theory as strengthening them. Results such as Arrow’s impossibility theorem, Gibbard-Satterthwaite’s theorem, or Sen’s Paretian-liberal paradox all display the same general lesson. Social choices cannot preserve the rationality that is assumed to hold at the individual level unless you give up on what we take as normally relevant conditions (e.g., non-dictatorship in Arrow’s and Gibbard-Satterthwaite’s theorems, minimal liberty in Sen’s paradox). In Sen’s paradox, keeping with all the conditions led to plain irrationality in the very sense of the overcompleteness interpretation (i.e., sometimes, no social choice will be possible). In Gibbard-Satterthwaite’s theorem, keeping with all the conditions entails that a voting rule is manipulable, which means that the social choice may fail to reflect appropriately individual preferences. In Arrow’s theorem, the conditions lead to an impossibility, and relaxing the controversial independence of irrelevant alternatives condition also opens the door to manipulative strategies.

Now, we don’t have to interpret the standard results of social choice theory negatively. An alternative is to take them as indicating that what is true at the individual level cannot and therefore shouldn’t be true at the social level. The inconsistencies and irrationality that we have good reasons to avoid for individual judgments and choice-making may not hold by social judgments and choice-making. I think however that this a view that may not be easy to reconcile with the kind of public reason liberalism that Gaus is defending in his work. Though they have since largely diverged,[6] Gaus’s public reason liberalism has common roots with Rawls’s own version. Rawls emphasizes the “burdens of judgments” to account for the unavoidability of pluralism in the liberal society. Rawls explicitly mentions Berlin’s value pluralism among the sources of these burdens:[7]

“any system of social institutions is limited in the values it can admit so that some selection must be made from the full range of moral and political values that might be realized. This is because any system of institutions has, as it were, a limited social space. In being forced to select among cherished values, or when we hold to several and must restrict each in view of the requirements of the others, we face great difficulties in setting priorities and making adjustments. Many hard decisions may seem to have no clear answer.”

Despite this reference, it’s not clear that Rawls's political liberalism endorses the full implication of Berlinian value pluralism. Coincidently, Gaus briefly mentions Rawls’s burdens of judgment in the chapter when he refers to the “derivative” understanding of the incompleteness interpretation.[8] Neither Rawls’s nor Gaus’s version of public reason liberalism is willing to accommodate value pluralism.

Why this is so is because value pluralism seems to be an obstacle to public justification, acknowledging that (in public reason accounts) public justification is a requirement to be satisfied if we want to establish the legitimacy of coercive political institutions. In the Rawlsian version, it is required that a consensus over principles of justice prevail, based on shared reasons that everybody can endorse from their “comprehensive doctrines.” Incommensurability cannot be total, for that would make such consensus hardly possible. Gaus’s version of public reason liberalism is less restrictive and demanding. People may disagree on the reasons justifying rules but what matters is that these reasons (e.g., religious versus secular) ultimately justify the same set of rules. Underdeterminacy (in the incompleteness interpretation) and overdeterminacy (in the overcompleteness interpretation) of public justification by reasons threaten however the very possibility that individuals’ reasons converge toward some set of shared rules. In Gaus’s terminology, value pluralism makes it more likely that the “eligible social set” (i.e., the set of rules that are publicly justified on some specific issue) is empty. If such a situation emerges, then the only possibility seems to be to more or less arbitrarily exclude some reasons (because they are unreasonable or unintelligible) from the public justification endeavor. But doing so could be charged with “sectarianism,” a critique that Gaus and his followers precisely address to Rawlsians.[9]

In his last book (posthumously published), Gaus develops a naturalistic argument to the effect that the emptiness of the socially eligible set is highly unlikely to happen and, what it does appear, it is in the case of a publicly justified “demoralization” of a specific issue (e.g., sexual practices).[10] The rules of social morality are the technology that humans have evolved to solve coordination and cooperation problems and, because of that, there cannot be too many situations where no rules are publicly justified, except for when everybody agrees that a type of behavior belongs to each private spheres. While this is a good point, I think this argument misses exactly what Eric points out regarding the existence of polarization or multiple social tribes/factions in society. Let’s put it more formally: on a social choice problem P (e.g., choosing a tax scheme or a regime of property), it may happen that within the whole population N the socially eligible set S is empty. That means that no rule happens to be publicly justified by the diversity of reasons that the members of N can advance, i.e., for each possible rule R, there is at least one person that has a decisive reason to prefer a no-rule situation to R. In this scenario, what can happen is a “fractionalization” of N into two or more subgroups N1, N2, …, each subgroup being able to agree on at least one publicly justified rule R1, R2, … You can interpret this outcome in two different ways. Either you view it as a case of secession where people form different autonomous societies. Or you can see it as a case of radical political conflict where an umpire (most plausibly, the state) is needed to adjudicate the conflict.

Note the implication if you retain the latter implication: the rule is not publicly justified and, implicitly, the umpire is acting in a sectarian way by ranking some reasons over others without any particular justification. All this can theoretically happen even without Berlinian value pluralism, but it is clear that if Berlinian value pluralism is a serious possibility (on either of its interpretations), this makes this scenario even more likely. These considerations led me to suggest that both Rawls’s and Gaus’s versions of public reason liberalism tacitly rely on a big assumption that I would call the Natural Harmony Hypothesis:

Natural Harmony Hypothesis – Underlying the moral world, there is a natural harmony of reasons such that human reasons are commensurate and convergent enough so they can publicly justify rules of social morality.

The opposite of the Natural Harmony Hypothesis is the Weberian view of the radical irrationality of the world, the “battle of the gods” that dramatizes political life as the realm of tragic choices that are out of the reach of full justification. Public reason liberalism is an optimistic account of the possibility of reconciliation in highly diverse and complex societies. Quite the contrary, the Weberian view has largely inspired a more skeptical liberal tradition, to which Berlin (as well as Berlin for instance) is traditionally associated.

Let me briefly conclude on what all this implies for Berlin’s “liberal pluralism.” In the chapter that we have been discussing, Gaus contemplates how Berlin’s pluralism and Berlin’s liberalism can be reconciled. He contends that Berlin’s liberal pluralism faces a dilemma: “to the extent Berlin is a pluralist, he is not a liberal; and to the extent he is a liberal, he is not a pluralist.”[11] Gaus is not the only one to reach this conclusion that value pluralism and liberalism go against each other.[12] In his case, however, I think the conclusion is largely driven by the Natural Harmony Hypothesis. For Gaus, the liberal society and its associated social morality are possible only because, at some level, the rational use of reason permits the discovery and the agreement over an overarching set of superior values. It’s right that Berlin himself appeals to such shared rationality and that’s why his view may indeed seem to be inconsistent. On the other hand, there is no reason to grant the Natural Harmony Hypothesis. This leads to a couple of interesting questions: can we conceive a kind of public reason liberalism that is more Weberian at the bottom? Isn’t a more “agonistic” conception of liberalism a more plausible approach to justify liberal principles and institutions in not only diverse but also highly conflictual societies? Deep questions, for sure!

*************************

As indicated at the very beginning, this essay was the last one of this academic year. I’ll take a well-deserved (?) three-week break in family in Slovakia. I expect to resume regular activities here by mid-August at the latest. However, since the audience of the newsletter has significantly grown over the past year and even more over the last 3-4 months, I thought it would be a good idea to republish old posts that were originally written when the number of subscribers was ridiculously low. Therefore, I will (automatically) publish during the coming month a selection of essays that I consider still relevant and interesting enough to be worth your attention during the summer. Expect to receive 4 or 5 of them in your mailbox. So, stay tuned!

[1] Gerald F. Gaus, Contemporary Theories of Liberalism: Public Reason as a Post-Enlightenment Project, First Edition (London ; Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2003).

[2] John Gray, Isaiah Berlin: An Interpretation of His Thought, Revised edition (Princeton University Press, 2020).

[3] Joseph Raz, The Morality of Freedom, Reprint édition (Oxford University Press, 1988).

[4] Gaus, Contemporary Theories of Liberalism, p. 39.

[5] Amartya Sen, “Incompleteness and Reasoned Choice,” Synthese 140, no. 1–2 (May 1, 2004): 43–59.

[6] See in particular Kevin Vallier and Ryan Muldoon, “In Public Reason, Diversity Trumps Coherence,” Journal of Political Philosophy 29, no. 2 (2021): 211–30.

[7] John Rawls, Political Liberalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), pp. 57-8.

[8] Gaus, Contemporary Theories of Liberalism, pp. 36-7.

[9] Jerry Gaus, “Sectarianism Without Perfection? Quong’s Political Liberalism,” Philosophy and Public Issues - Filosofia E Questioni Pubbliche 2, no. 1 (2012).

[10] Gerald Gaus, The Open Society and Its Complexities (Oxford University Press, 2021).

[11] Gaus, Contemporary Theories of Liberalism, p. 50.

[12] John Gray defends it too. See Gray, Isaiah Berlin.

Thank you! Very nicely done

“The Natural Harmony Hypothesis […] assumes that human reasons are commensurate and convergent enough to justify social rules, which is overly optimistic and fails to account for the deep-seated and real, multidiemnsional material resources conflicts and value pluralisms present within large human social spaces.”

Another interpretation might be that as societies grow larger and inevitably more diverse, the scope of truly social rules is reduced. But we can hardly imagine that this process might advance so far that agreement on the prohibition of arbitrary killing would be lost. If allowed to adjust to this tendency, people might end up with large societies that share a few very general rules, while at a smaller scale societies or associations emerged that had more extensive agreement on rules, a sort of natural federalism or subsidiarity.

“By forcing economic integration, liberalism inadvertently undermines the social cohesion and cultural diversity that are essential for a vibrant society.”

Wouldn’t it be more accurate to say that by *allowing* economic integration, liberalism inadvertently undermined the social cohesion and cultural diversity that are essential for a vibrant society? No one held a gun to the heads of companies that merged.

It is not entirely clear what is meant by the separation of social and economic spheres, or what the envisioned alternative is. Making a wild guess, perhaps it means that the social consequences of economic policies were not foreseen accurately, or were foreseen but disregarded; and the alternative would task policy makers with making more accurate predictions of the consequences of their policies, and deciding things more in line with the preferences of… someone other than those who preferred past decisions.