Rawls’s Difference Principle, Neighborhood, and Rigid Designators

In an appendix of Parfit’s Reasons and Persons, John Broome briefly discusses Rawls’s difference principle, emphasizing an inconsistency between the way Rawls characterizes this principle and how he accounts for it. Broome starts from Rawls well-known definition:

“Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are… to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged” (Rawls 1971: 302).

Broome argues that this definition is not consistent with what Rawls seems to want to hold. He takes the following example, where it is assumed that all primary goods are distributed between the population of two countries (India and Great Britain) equally but for social and economic well-being, which distribution differs depending on the constitution that could be adopted:

Rawls’s difference principle, characterized here as being equivalent to the maximin criterion, plausibly favors Constitution 3. However, Broome notes that it is not consistent with the above formulation of the difference principle: “The least advantaged under Constitution 3 are the Indians, and the greater inequalities under [Constitution 3], compared with [Constitution 2], are not to the benefit of the Indians. They would have been better off under [Constitution 2]” (Parfit/Broome 1984: 492).

Broome goes on to argue that when pushing for the difference principle, Rawls several times uses a wording that corresponds to the idea that inequalities must be “to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged”.[1] However, in many cases as in the example above, this leads to a tension between the difference principle stated this way and the difference principle understood as an instance of the maximin criterion. Broome concludes that according to Rawls’s formulation, individuals’ benefits and burdens should be weighed against each other, i.e., the losses Indians suffer from substituting Constitution 3 for Constitution 2 against the gains Britons enjoy from the same substitution. Understood this way, the difference principle rather looks like an aggregative principle, not so much different than the utilitarian one for instance.

Rawls offers a rebuttal to Broome’s criticism in Justice as Fairness: A Restatement (Rawls 1999: 69-72). He develops two complementary arguments in favor of his formulation of the difference and against Broome’s claim that this formulation is inconsistent with the use of the maximin criterion in distributive conflicts:

(1) The statement and the use of the difference principle should exclude the use of rigid designators, i.e., names referring to the same individuals, organizations, or countries in all possible worlds.

(2) A social arrangement (a “constitution” in the above example) should only be compared with alternative social arrangements located within its neighborhood.

I shall start with argument (2) and set aside for the moment argument (1) against the use of rigid designators. According to Rawls, Constitution 3 should not be directly compared with Constitution 2 as the difference in terms of distribution of well-being presumably underlies significant differences between the two respective basic structures. In this perspective, Constitution 3 seems to be closer to Constitution 1 and if a comparison must be made, then the latter is more relevant. Rawls articulates the idea of neighborhood with the notion of reciprocity: increasing economic inequalities are potentially justified if they respect the reciprocity that is at the core of a society defined as a fair scheme of cooperation. That is, a social arrangement leading to economic inequalities is justified if it can be shown that they satisfy this reciprocity requirement. Now, comparing radically different social arrangements such as Constitution 2 and Constitution 3 it might be plausibly assumed you cannot go from 2 to 3 or from 3 to 2 while satisfying the reciprocity requirement: the Indians’ (resp. the Britons’) losses cannot be seen as an expression of a reciprocity relationship with the Britons (resp. the Indians) who enjoy additional benefits. Hence, Constitution 2 and Constitution 3 should not be compared.

As Rawls recognizes, this argument assumes that there is a “rough continuum of basic structures, each very close (practically speaking) to some others in the aspects along which these structures are varied as available systems of social cooperation” (Rawls 1999: 70). Otherwise, no comparison would be possible, and the difference principle would be empty. Thus, assume that such a continuum exists. However, Rawls’s continuum assumption does not resolve the problem. We can proceed with a little formalization. Denote N the binary relation “is in the neighborhood of”. We can plausibly assume that this relation is symmetric, i.e.,

Suppose that there exists a set of n social arrangements such that, for any arrangement x, there are at least two arrangements y and z such that xNy and xNz but not yNz, i.e., each social arrangement as at least two neighbors which are not themselves neighbors. We add a further assumption: any two social arrangements can be “connected” by passing through a sequence of social arrangements such that for any arrangement {x_i,…, x_i+m} in the sequence, we have x_k-1,Nx_kNx_k+1. Now, if we grant Rawls’s suggestion that constitutions 2 and 3 are not in the same neighborhood, we know nonetheless that two constitutions can be connected by such a sequence. Say that arrangement x_i is directly favored to arrangement x_j according to the difference principle if and only if:

While Constitution 2 and Constitution 3 are not neighbors, Rawls seems however to suggest that they still belong to the same sequence: there is a sequence of arrangements such that at least one arrangement is a neighbor to Constitution 2 and has a neighboring arrangement that has a neighboring arrangement… which has as neighbor Constitution 3. This would make it possible to make iterated comparisons of social arrangements until we reach the one that must be favored by the difference principle. Say that two social arrangements x_i and x_j can be indirectly compared if they are not neighbor but are arranged in the following way:

A pair of social arrangements can be indirectly compared if and only if

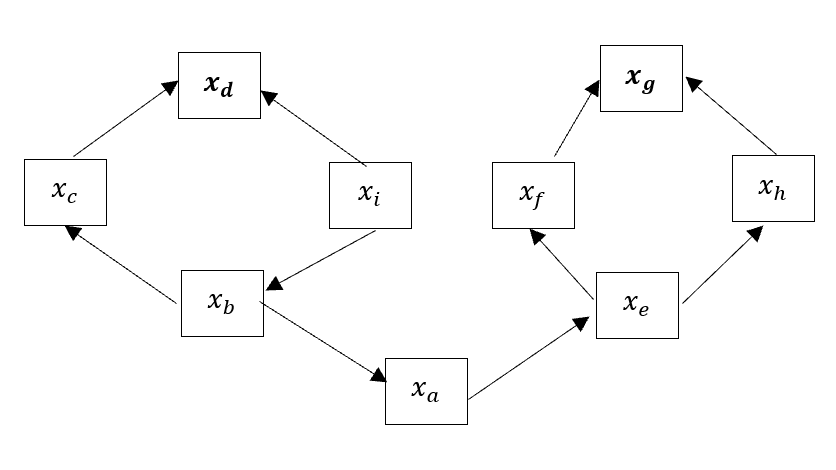

(a) just is the assumption of connectedness corresponding to Rawls’s ideal of a “rough continuum” of social arrangements. Condition (b) guarantees that as we “pass-through” the sequence, each subsequent arrangement is better than the preceding according to the maximin criterion. Condition (c) guarantees that there is no local optimum. A graphical example illustrating what happens when these conditions are not satisfied is given below (an arrow indicates that the two social arrangements are neighbors with the arrangement at the end of the arrow the better one according to the maximin criterion):

In this example, suppose we want to compare arrangements x_d and x_g. There are four sequences connecting them, for instance {x_c, x_b, x_a, x_e, x_h}. Suppose that x_g is Constitution 2 and x_d is Constitution 3; thus, the former is better than the latter according to the maximin criterion. However, conditions (b) and (c) are both violated: no neighbor is better than x_d which thus is a local optimum; moreover, there are sequences where a social arrangement is worse than all its neighbors (e.g., x_b in the sequence {x_c, x_b, x_a, x_e, x_h}). Therefore, we see that assuming a “rough continuum” of social arrangements is not sufficient. Rawls’s argument requires very specific structural conditions on the “landscape” of social arrangements. Indeed, in the example above, if we are in social arrangement (Constitution 3), there is no way to convince the Indians that adopting Constitution 2 (arrangement ) will “arrange economic inequalities to the greatest benefit of the least advantages” because all neighboring arrangements are indeed worse in this respect.

All these complexities arise from the fact that we are using rigid designators. But as Rawls repeatedly warn, the use of the difference principle should not rely on rigid designators: parties should not be identified by their names or any other intrinsic properties that are constant across all possible worlds, but by their relative positions in terms of primary goods. If we accept this claim, Broome’s example now reads as follows:

This obviously makes the difference principle more appealing and consistent with the maximin formulation. The best argument for the exclusion of rigid designators is that the difference principle is chosen under the highly particular conditions of the original position where individuals ignore everything about their personal characteristics. This is thought to capture the fact that “the difference principle does not appeal to the self-interest of those particular persons or groups identifiable by their proper names who are in fact the least advantaged under existing arrangements” (Rawls 1999: 71). This makes the exclusion of rigid designators conditional on the acceptance of the veil of ignorance as the proper device to capture impartial reasoning about justice principles. This is debatable of course. We may want to be able to identify each party’s claims and then weighed them in an impartial fashion. This is actually a reasonable requirement from a contractualist perspective. A weaker “anonymity condition” according to which names are irrelevant in the statement and justification of justice principles may be more appropriate. In Broome’s example, that would mean that nothing changes if we switch Indians’ and Britons’ positions. This guarantees that no party is given any favorable treatment just because of his identity. The problem is that in the justificatory endeavor, the justification of inequalities to parties (individuals or social groups) may require accounting for their situations with respect to two dimensions: their relative positions compared to other parties and, maybe more significantly, their relative situations compared to how they could have fared off in another “accessible” social arrangement. Therefore, it is hard to see how justification can then proceed as the anonymization of parties removes all this information. The only remaining solution is to follow Rawls and assume that expectations are chain-connected. As I have explained in a recent post, this assumption is however also problematic, at least in contemporary Western societies.

[1] Admittedly, this is not the case when Rawls defends the difference principle under the veil of ignorance, as Broome recognizes.