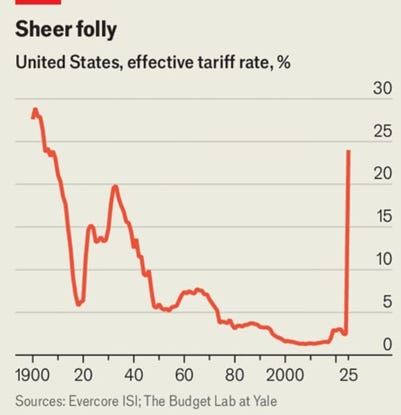

As one picture can be worth dozens of words, let’s start with the following figure (source):

So-called “Liberation Day” arguably marks the most significant increase in tariffs in over a century. It is even more striking as it takes place against a background of several decades of institutionalized globalization where states, starting with the U.S.A., have methodically suppressed all barriers to international trade. As it happens, I’m currently reading the intellectual historian Quinn Slobodian’s history of this process that started in academic circles during the interwar period and took concrete shape with the creation of international institutions after 1945.[1] Slobodian defends an interesting thesis. Contrary to what many critics have argued, the objective of the “neoliberal” intellectuals who first defended the abolition of trade barriers (Mises, Hayek, Röpke among others) was not to “dis-embed” markets from the rest of society. Rather, the point was to “encase” global markets in a set of rules that would immunize them against arbitrary interference from social and political actors. That was a political project that was not betting on the spontaneous properties of markets to spread across the world but, quite the contrary, was well aware that markets need to be institutionalized by political and legal means.

Interpreting Trump’s protectionist U-turn in this light is quite interesting. It participates in a more general political trend that I’ve identified and characterized several times in this newsletter (see here for instance). A defining feature of modern populism is the myth that the People will take back control of their lives. The open society is organized around general rules that constrain and liberate impersonal forces that affect individuals’ daily lives without, most of the time, the effects being intended by a person or a group of persons. International trade is one of those typical forces. As goods and capital are circulating across borders as a result of the forces of supply and demand, economies change and have to adapt. Some factories close here and others open there. Some people lose their jobs in this region, and others find new job opportunities in that part of the world. Not only economic life, but life prospects in general are eventually left at the mercy of contingent factors that nobody seems to control.

The “neoliberal” bet was that the institutionalization of a global economy, putting as few constraints as possible on these impersonal forces, would be to the advantage of everyone. There were good arguments for that and, in many respects, the bet has somehow been a success. However, not everybody has won, and there is no doubt that the adverse effects created by unconstrained global markets have been underestimated. In any case, Trump’s “Liberation Day” announcement marks the end of this era. We are now entering a world where global markets are no longer protected from the arbitrary political interventions that are motivated by more parochial concerns. This is clearly true in the U.S., but it is also likely to set the tone for the rest of the world.

Consider the case of the European Union more specifically. Over the last couple of days, there have been a lot of talks about possible retaliation. Some of them are direct and would take the form of “reciprocal” tariffs on U.S. goods. Others are more indirect but clearly triggered by Trump’s commercial attacks, such as increasing the pressure on the GAFAM to conform to EU regulations. Talks of retaliation validate the idea that an “economic war” has started. However, the very idea that something like an economic war is possible is flawed, and that should lead European officials to think twice before fueling a nonsensical mutually destroying escalation.

I don’t think I need to argue in any detail that the Trump administration’s new trade policy has absolutely no economic justification. As the economist Jason Furman mockingly remarks in a recent NYT op-ed, the Trumpian logic according to which trade deficits signal that one has been “screwed” or “exploited” by those to whom they are buying goods is nonsense. It is clearly absurd at the level of the individual consumer or worker, and there is no argument to suggest that it should be different at the level of national economies. If anything, Americans should be glad that they are able to find foreign partners able and willing to sell them goods at prices they can afford. What makes you rich and improves your well-being is what you can consume, not what you sell. As all economic students know (or should know), the only reason why countries are interested in selling their goods abroad is because they can buy goods of other countries in exchange at some point. Currencies are useless if they cannot be converted into stuff that satisfy people’s preferences. Exporting cannot therefore be an end in itself. To view trade surpluses as the ultimate goal of your trade policy is like saying that, as an individual entrepreneur, your goal is to sell as much as possible but not spend the money to buy anything from other companies because then you would have a “trade deficit” with them.

This is not to say that trade imbalances cannot have real economic consequences, some of them adverse for part of the population. Millions of U.S. workers lost their jobs because it is cheaper to buy some goods abroad than to produce them at home. The large majority slightly benefits from an optimal localization of productive activities, but a more or less significant minority is seriously harmed. But there is no evidence that protectionist policies, especially of the kind promoted by the Trump administration that blindly raises tariffs for all partners, are likely to help. The only plausible argument is that such policies will encourage producers to (re)locate to the U.S. territory. That may be true at the margin, but it will take time (months if not years), and the positive effects in terms of jobs and purchasing power are likely to be insufficient to compensate for the large adverse macroeconomic consequences to be expected. In any case, I don’t know of any theoretical model or empirical study that suggests that there is even a tiny chance that that could work.

Now, once we acknowledge all this, how can we make sense of the idea of retaliation from the E.U.? We can certainly understand the emotional appeal of this “Talion law.” More theoretically, we could say this is part of a tit-for-tat strategy that aims at incentivizing the Trump administration to revert to a more reasonable cooperative trade policy. However, the analogy is dubious. Tit-for-tat strategies make sense in what game theorists call positive sum games, i.e., in situations where everybody can gain by cooperating. In these situations, it pays off to stop cooperating when the other doesn’t cooperate. It doesn’t apply here because the Trump administration has credibly committed to sticking to its madman strategy, at least as far as trade policy is concerned. We are therefore definitely engaged in a negative sum game. In these circumstances, retaliation will only make the situation worse for everybody, including for European citizens and consumers. Protectionism is never the best response, whatever other countries are doing, especially if there is no decent prospect that others will make a step back in their protectionist folly.

Engaging in massive retaliations would only validate the Trumpist belief that international trade is nothing but a war, without any positive effect in sight. This belief would become a self-fulfilling prophecy, destroying the rule-based order that has been patiently constructed since WWII. When you’re confronted with a negative-sum game, the best you can do is to avoid playing it as much as you can. For sure, this is not so easy and it will take time, more time at least than simply raising tariffs on American goods. In any case, the U.S. represents less than 15% of the global final demand for imports and has not been the key driver of global trade growth for two decades. The U.S. economy is central to the world economy, but not that central. The most promising perspective is to count on a progressive reallocation of resources toward other trade partners, within the E.U. and between the E.U. and other economies. At a more formal level, the best response is to look for new trade arrangements with partners other than the U.S., though it is unlikely that E.U. countries will be willing to do it with the most important of them, i.e., China.[2] The biggest difficulty will be to resist popular pressures to implement quick-and-dirty countermeasures, though hopefully most people intuitively understand that that could only have detrimental consequences.

In any case, there is no way to avoid the damages caused by Trump’s protectionist U-turn. The best that can be done over the short run is to avoid engaging in a costly and unproductive trade war and, over the mid-run, to try to preserve the economic institutions but also the “philosophy” that has permitted the positive effects coming with the globalization of economies since WWII.

[1] Quinn Slobodian, Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism (Harvard University Press, 2018).

[2] Eswar Prasad, “The Age of Tariffs,” Foreign Affairs, April 3, 2025, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/age-tariffs-trump-global-economy.

I think there is an analogy to Putin's invasion of Ukraine, which also seemed a "madman strategy." In the beginning, many in Russia thought so also, but the relatively soft pushback encouraged them to think that their only choice is to support Putin.

Similarly in the US, the EU should be looking past Trump, and considering how to prevent Trump from consolidating autocratic rule in the US. Not pushing back would play into Trump's narrative, while sufficient pushback now may shatter Republican morale.

Already an aggressive invasion in Europe should have been more than Europe was prepared to live with. If they are prepared to live with Trump now, their days as liberal democracies are numbered.