Social Practices and the Harm Principle

The Tale of a Liberal Idea Turned Into an Illiberal Weapon

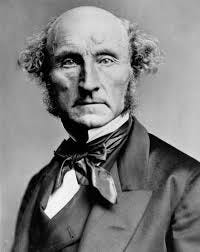

In On Liberty, John Stuart Mill famously formulated a principle that was to become a staple of liberal thought:

“That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually, or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action any of their number, is self-protection. That only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”[1]

There have been literally thousands of pages on what is now called the “harm principle.” The idea is simple on the surface. The principle is especially designed to rule out all forms of paternalism, especially from the state. More generally, the principle creates private spheres where individuals should be free from the exercise by others of their coercive power. The harm principle is therefore important in the perspective of defining what political philosophers sometimes call “jurisdictional rights,” i.e., rights that literally create a “personal jurisdiction” within which the individual is sovereign. Jurisdictional rights partition the moral space by allocating domains to individuals in which they do not depend on the will, preferences, or actions of others.[2] If we adopt a public reason framework (which was obviously not Mill’s), the effect of jurisdictional rights is to circumscribe the domain where the public justification requirement operates. The idea is that if an issue falls within a person’s personal sphere, as delimited by her jurisdictional rights, then what she does (or the principles/rules that she decides to follow) is not subjected to the requirement of being publicly justified to others. What must be publicly justified is the partition of the moral space as delineated by the system of jurisdictional rights, but once rights are defined, one is free to act as she wishes as long as she stays within the bounds of the area defined by her rights.

The concept of jurisdictional rights largely echoes what Benjamin Constant called the “liberty of the Moderns.” For Constant, individual liberty in the modern sense entails the ability to benefit from one’s independence from others. But this independence exists only in so far as we collectively agree on limits within which nobody can interfere. Property rights, rights of association, or privacy rights are from this perspective all jurisdictional rights.

There are many ways to define a system of jurisdictional rights and my contention here is that Mill’s harm principle provides a (publicly endorsable) principle to do so. This is surely not the only one in town – think for instance of principles derived from natural rights theory. The harm principle closely ties rights to interests. This is indeed made explicit by Mill:

“Though society is not founded on a contract, and though no good purpose is answered by inventing a contract in order to deduce social obligations from it, every one who receives the protection of society owes a return for the benefit, and the fact of living in society renders it indispensable that each should be bound to observe a certain line of conduct towards the rest… As soon as any part of a person’s conduct affects prejudicially the interests of others, society has jurisdiction over it, and the question whether the general welfare will or will not be promoted by interfering with it, becomes open to discussion.”[3]

This paragraph nicely states the relationship between the jurisdiction defined by rights and individuals’ interests. The harm principle proposes that jurisdictional rights should be defined such that one’s domain of individual sovereignty is coextensive with one’s interests. When one’s action reaches beyond one’s interests, “society has jurisdiction over it.”

I said above that the principle is simple enough at the surface. But when we scratch this surface a bit, innumerable complexities arise. In some cases, the harm principle has been twisted to allow for paternalistic interferences.[4] More relevant to my discussion, there is an obvious difficulty with how we identify individuals’ interests. Since rights and interests are coextensive, if we disagree on the characterization of individuals’ interests, we will hardly agree on the right-based partition of the moral space. One source of the problem is that the identification of interests is relative to a certain underlying ontology. For instance, one’s attitude toward abortion depends on how one perceives the ontological status of the fetus. Does the fetus have rights? It plausibly depends on whether the fetus is a human being or not. The fact that individuals may hold radically different perspectives on many moral issues makes a publicly agreed definition of jurisdictional rights complicated.[5] Even if individuals share common perspectives, the definition of rights may be blocked by a disagreement over what counts as what economists would call “externalities.” If I play drums at 11 pm every evening, a sensible case can be made for the claim I’m infringing you’re right for tranquility. Or maybe – less plausibly – we can agree that I’ve the right to play whenever I want. Whatever the case, if we agree upon the definition of rights, there is no real difficulty in principle. Individuals can bargain to internalize the externality – we recognize that our interests conflict and that our mutual actions (me playing drum, you forbidding me to play) are prejudicious to our respective interests, and we find a mutually advantageous agreement (e.g., you pay me to not play). However, that works only if we explicitly or implicitly on the partitions defined by rights. If you “bribe” me to not play, that means that you implicitly accept that I’ve the right to play. No bargaining is possible however if there isn’t an ex-ante agreement on rights.[6]

This leads to the third difficulty. Critics of liberalism tend to develop an argument that goes something like this

1/ The liberal society L promotes (or facilitates) the emergence and development of a practice P consisting of a myriad of not necessarily related actions A from a set of individuals N.

2/ This practice adversely affects the interests of a different set of individuals N’ by rendering their practice P’ impossible or ineffective.

3/ Therefore, P should be prohibited.

4/ Since P cannot be prohibited under L, we should abandon L.

My view is that this kind of argument underlies a lot of recent critiques of liberalism, including notably Patrick Deneen’s one that I’ve discussed a couple of weeks ago.[7] Note how the argument follows the line of the harm principle. It identifies individuals with interests and claims that, because these interests are adversely affected by other persons’ behavior, the latter should be interfered with. There is a significant difference though. At no point is it claimed that an individual’s personal action directly and adversely affects another’s interests. It is rather the fact of participating in the practice that is indirectly detrimental. The practice P consists of a set of actions A but really what is problematic is not that some individuals do A, but rather that doing A has been institutionalized by P.

Consider the case of pornography. That one person watches pornography does not directly affect anybody else’s interest. The fact that Ann (or Brian) chooses to watch pornography or not at some point does not change anything. The practice exists and the harm caused, if any, is really due to its existence, not because one person has decided at one moment to participate in it. True, a practice couldn’t exist without individuals’ actions that are constitutive to it. But as formulated by Mill, the harm principle is purely individualistic. If one’s action has no or marginal effect on others’ interests, there is no ground for interfering with it. The illiberal version of the harm principle applies the argument to social practices and is in this sense “collectivistic.”

Some would say that this is sufficient to disqualify the whole argument, but this is unfortunately not so straightforward. First, as Rawls famously argued, that an action can be justified as being part of a practice is not the same as justifying the practice.[8] In this article (written before Rawls had completely set his mind on his “justice as fairness” account), Rawls suggests that the justification of practices can be subjected to a utilitarian criterion. Hence, even if we accept that participating in P doesn’t infringe upon anyone’s right, there could still be a case for interfering with P if it happens that P is really detrimental for many in the population. Second, and more worryingly, some liberal authors themselves have dangerously been close to validating the collectivistic version of the harm principle. Consider for instance how Jason Brennan characterizes what he calls a “collectively harmful activity (CHA):”[9]

Define a “collectively harmful activity” as an activity in which a group is imposing or threatening to impose harm, or unjust risk of harm, upon other innocent people, but the harm will be imposed regardless of whether individual members of that group drop out. It’s plausible that one might have an obligation to refrain from participating in such activities, i.e., a duty to keep one’s hands clean.

Note an important point in this definition: the harm does not depend on one’s participation in the activity. Still, Brennan claims that one may have an obligation to refrain from participating, especially if the costs are low. Brennan uses this argument in the context of his critique of the ethics of voting. To vote is to participate in a widespread democratic practice. Though the marginal effect of your vote is null, the fact that you participate in this harmful practice indirectly contributes to harm many persons. Therefore, you’ve the obligation not to vote.[10]

The argument seems close to the collectivistic version of the harm principle. Indeed, some of Substack have suggested that it applies to pornography. In some sense, economists’ reasoning about market failures is also really about CHA. The worry is that if we allow for this kind of reasoning, it compounds with the two first difficulties I’ve highlighted. The harm principle seems then to open the door to all kinds of interference and, ultimately, to be antithetical to the definition of jurisdictional rights. This is exactly what happens when antiliberal critics endorse it.

From the liberal point of view, we either have to ditch Mill’s harm principle or provide a convincing argument against the collectivistic version. Regarding the latter route, a possibility is to argue that the concept of CHA should be restricted to practices that involve a form of collective or shared intentionality.[11] We-intentional practices are such that they generate a collective action that is more than the sum of individual actions. For instance, persons who intentionally coordinate to destroy a common resource, even though each of their individual actions has a marginal effect, should be plausibly forbidden to do so. Collectively intentional practices that cause harm plausibly falls within the scope of the harm principle. However, neither voting nor watching pornography seems to qualify as collectively intentional practices in this sense. So, maybe the harm principle can be saved from its illiberal implications after all.

[1] John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, Utilitarianism and Other Essays, ed. Mark Philp and Frederick Rosen, Second edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 12-3.

[2] See for instance Gerald Gaus, The Order of Public Reason: A Theory of Freedom and Morality in a Diverse and Bounded World, Reprint edition (Cambridge New York,NY: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 370ff.

[3] Mill, On Liberty, Utilitarianism and Other Essays, p. 73.

[4] See especially Joseph Raz, The Morality of Freedom, Reprint édition (Oxford University Press, 1988). I must admit that I’ve always had difficulties with Raz’s argument, which entails a reformulation of the harm principle which ends up in something completely different than Mill’s account.

[5] For a formal treatment of this issue, see Hun Chung and Brian Kogelmann, “Diversity and Rights: A Social Choice-Theoretic Analysis of the Possibility of Public Reason,” Synthese 197, no. 2 (February 1, 2020): 839–65.

[6] This is an important point discussed in detail by James Buchanan’s contractarian account of the limits of liberty, see James M. Buchanan, The Limits of Liberty: Between Anarchy and Leviathan (University of Chicago Press, 1975).

[7] Patrick J. Deneen, Why Liberalism Failed, Reprint edition (New Haven London: Yale University Press, 2019).

[8] John Rawls, “Two Concepts of Rules,” The Philosophical Review 64, no. 1 (January 1955): 3.

[9] Jason Brennan, “The Ethics and Rationality of Voting,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2020 (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2020), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/voting/. The quoted paragraph is the fourth of section 3.2.

[10] I will abstain from judging the plausibility of Brennan’s argument against voting.

[11] For an account among many others, see e.g., Raimo Tuomela, “We-Intentions Revisited,” Philosophical Studies 125, no. 3 (September 2005): 327–69.

I think utilitarianism has always been collectivist in its essence, it simply that that aspect was not emphasized or not discovered yet in Mill's time. Utilitarianism absolutely justifies taxing Elon Musk's entire wealth and spending it on malaria nets in Malawi.

But in Mill's time, collectivist ideas were coming from conservatives, and liberals were individualists, because the basic liberal assumption was that only the government has any real power, make the government small and power or oppression does not happen.

After that time other kinds of power were quickly discovered, and then people thought if you use the government against this or that power, there will be less oppression and more freedom.

Is there a good way to specify the boundaries of interest? There exist busybodies who disapprove of nearly anything, and anything that escapes their interests might be considered a benefit by yet others, making it of interest to them. I am quibbling, but whether this means that we should stipulate an appropriate definition of interest or use a different concept or word, or come up with a better concept, I am not sure.

In other words, interests are not necessarily physical, nor even objective. I think the norms we use to answer such questions has to rest on justice rather than interest.

This all tempts me to complain about the harm principle, since for it to work, harm must be considered a normative and subjective thing. If harm is objective, sparring in a martial arts gym or boxing should be prohibited, because physical harm is nearly inevitable. The critical factor is that it is consensual harm, a risk taken willingly. And this leads to even more questions, even further from the post topic.