The Machine Process, the Fear of Redundancy, and the End of Politics

Speculations Based on a Recent Greg Egan’s Short Story

Warning: What follows contains a major spoiler of one of the recent short stories by sci-fi author Greg Egan, “The Discrete Charm of the Turing Machine.” If you’ve not read the story but would like to, read it before reading this post.

The sci-fi writer Greg Egan published in 2017 the short story “The Discrete Charm of the Turing Machine.” Egan is well-known as probably the most influential contemporary hard sci-fi writer and as an occasional sci-fi reader, I have been enjoying his stories for almost a decade now. Egan’s stories generally make use of deep conceptual reflections related to physics, mathematics, or philosophy. Among the short stories that have left an impression on me,[1] I must mention notably “Luminous” which tells the story of the encounter of two different mathematical realities, and “Unstable Orbits in the Space of Lies” which describes a universe where beliefs become geographical attractors, people’s beliefs evolve as they move from one location to the other.

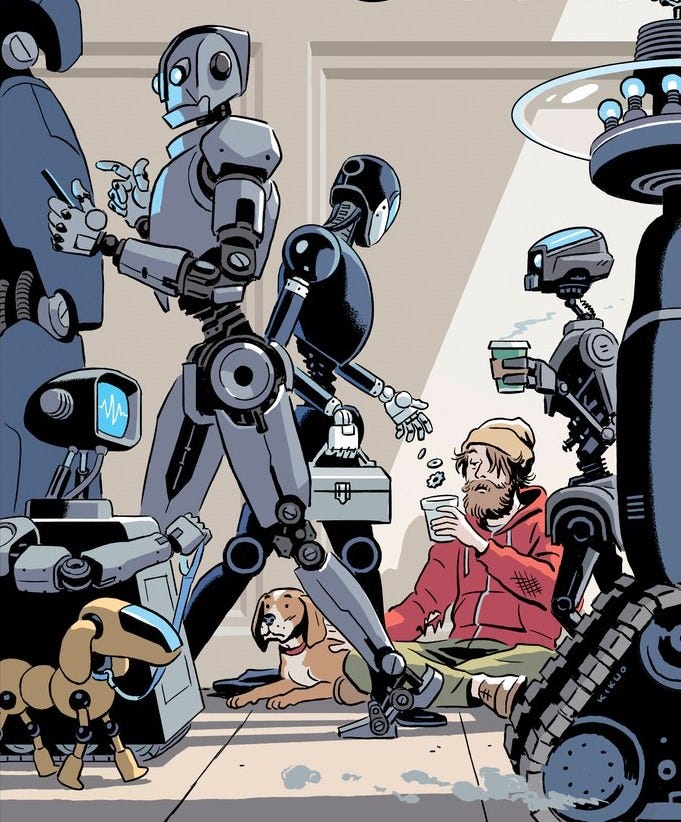

© R. Kikuo Johnson for The New-Yorker

“The Discrete Charm of the Turing Machine” displays the same concerns about new technologies' individual and social consequences as in many other Egan’s stories. The premises of the story are now familiar. We read about how the life of a normal family is challenged by the progressive substitution of machines for human work, including for “intellectual” tasks that seem to rely on human creativity. What makes the story interesting is the plot twist that the reader can progressively see coming and that Egan introduces explicitly at the very end of the story. [Spoiler begins] In the face of the disastrous economic and social consequences of the progressive disappearance of human jobs, governments, and the tech industry have somehow agreed to implement something akin to a universal income but without direct cash transfer. Some companies rather specialize in offering services to other companies consisting of creating an artificial demand so that humans who have lost their jobs can continue to work for anonymous “customers” who regularly buy, for instance, cakes or novels. The cakes are however never eaten, and the novels are never read; they are thrown in the garbage by the “customers” as soon as they receive them, but their producers are never aware of that. People therefore have the illusion of still having a role in society and they receive the needed income to consume the products produced by machines. [Spoiler ends]

Egan obviously leaves many details aside and we may wonder if the kind of economic arrangement he alludes to would be workable. But the point of Egan’s story is elsewhere. Since the industrial revolutions, economists have been concerned with the possibility of so-called “technological unemployment.” Technological progress tends to trigger a substitution of capital for labor and of qualified labor for non- (or less) qualified labor. The fear that human jobs will disappear as a result is famously captured by “Luddism” and has been continuously expressed throughout the last century. Until now, this fear has not materialized. People are still working, and unemployment has not significantly increased in developed economies since we have the means to measure it.[2] Of course, historical patterns are not necessarily a good indication of what will come next, and the emergence and progress of artificial intelligence may indeed inaugurate a qualitative change in the relationship between technological progress and employment. We can indefinitely speculate about this and we’ll not know before the future becomes the present.

I think that Egan’s story also conveys the more interesting idea that technological progress, especially the emergence of AI, pushes individuals to reconsider their social role and, by extension, what makes them singular as intentional and intelligent beings. In Egan’s story, the underlying economic arrangement not only has for vocation to provide people with the necessary income to survive and to keep the economic system afloat. If that was the only purpose, there would be no point in keeping this arrangement secret.[3] The arrangement works because it gives the illusion to people that there is still some use for their capacities and, more generally, that as humans, they still have something distinctive to provide society with. It is interesting that the kind of activities that, in the story, are still made by humans (though in the end, they have no other purposes than occupying their authors) are creative activities (cooking a cake, writing a novel). Creative activities are precisely those for which humans believe they have a distinctive ability that distinguishes them from machines (and eventually, from other humans).

I think all creators of any kind (be they writers, artists, cooks) have this sense of uniqueness and singularity. What they create is theirs and could not have been made by anyone else. Whether this is true or not is not the point. Humans take pride in creating because they see it as a distinctive human activity and because it contributes to defining who they are as persons. The culmination of the “machine process” (to use an expression from the economist American Thorstein Veblen) in the emergence of AI is thus more than an economic issue. It is also an existential and anthropological one. The fear is not only that humans could become economically redundant but that they could become redundant tout-court, thus questioning their very status as singular intentional entities.

In a previous essay, I conjectured that the emergence of AI could mark a further step in the Weberian “disenchantment of the world” due to the never-ending rationalization of human practices:

“The progress of AI also leads however to a different kind of disenchantment, which may be even more fundamental. The rationalization process may have forced the retreat of mystical beliefs to the private sphere, but at least it was still possible to believe that what makes being a human cannot be fully rationalized. Imagination, creativity, understanding, or meaning were thought to be human properties defying prediction and systematization. You can rationalize the organization of society, not the organization of human minds. But more and more this appears not to be true. Not only AI is able to predict our behavior. They can reproduce it and even maybe improve it, including in domains where genuinely human qualities are at stake. ChatGPT or Midjourney is far from being a perfect substitute for the human mind. But it is highly likely that one day they will be able to reproduce exactly the qualities that define us. It will then be obvious that our mind has nothing special but quite the contrary can be fully emulated and rationalized. This poses a real existential question. In a world where everything is rationalized, including our thoughts and in general, what is happening in our “inner world”, where is the retreat for our “mystical” beliefs? On this view, the hypothetical emergence of artificial general intelligence would not only change our society and the conception we have of it, but it would also change our conception of ourselves and therefore also probably change us. It would have to be seen as the culmination of the process that started some six centuries ago.”

I think Egan’s short story conveys if only implicitly, a similar concern. If we take this idea seriously, it is worth pondering the implications. In the Weberian account, the rationalization of human practices entails in a way the end of politics, formal rationality and the blind adherence to rules being a substitute for the unsolvable conflicts of values that mark the political realm. However, other forms of authority (traditional and especially charismatic) never fully disappear however and can reemerge to shake the “iron cage” in which human beings are trapped. There are many ways through which the machine process can reinforce the iron cage by robbing individuals of their beliefs (illusions?) that the adherence to values proceeds from a creative and ultimately non-fully rationalizable choice. AI can already be used to nudge if not manipulate people’s normative beliefs and, in some not-so-sci-fi scenarios, could be used as a plain substitute for persons’ value judgments.

In such a disenchanted world, people’s retreat from politics and more generally from public life would be almost complete. For, what would be the point of participating in it? The alternative seems therefore to be between living under the Eganian illusion of the modicum of human relevance and a world ruled not by machines but by full-fleshed humans using their charisma to reintroduce the minimum amount of mysticism and “arationality” needed for social public life to be preserved.

Well, this is arguably a very dystopic view and hopefully, this scenario will remain a (science-) fiction. That doesn’t mean that thinking along these terms is irrelevant to understanding the prospects and the risks of technological progress, quite the contrary. History is open-ended and the best way to navigate through uncertainty is to explore the possible futures. Marrying fiction, science, and philosophy is the best way to do this.

[1] Interestingly, I’m in general less impressed by his novels. That may be because the short stories are often organized around a deep philosophical point while the novels tend to be less focused or introduce too many less relevant details.

[2] Though it should be noted that people work less per year and throughout their life – especially because young people stay longer at school. In this sense, technological progress has indeed reduced the quantity of human labor needed. By conventional normative standards, these are however positive changes.

[3] It is not said in the story that the arrangement is intentionally kept secret by the government and companies. It may be that the arrangement has spontaneously emerged and that (almost) no one has identified it. The very end of the story suggests however that the arrangement would no longer continue to function if too many persons were to become aware of it.