Kamala Harris has started unveiling some aspects of her economic program in advance of the coming U.S. Presidential elections. The propositions briefly mentioned all target the problem of the rising costs of life, which is certainly sensible as inflation is among the main preoccupations of American voters. Harris has proposals to reduce housing and medical costs, as well as taxes. But it’s her plan on groceries’ costs that has attracted the most attention – and criticisms. Harris is proposing to ban so-called “price-gouging” on groceries. Most political and economic commentators have criticized the proposal as an inefficient and potentially harmful way to fight inflation.[1] Still, we may hope that Harris has economic advisors who know as well basic economic principles as the rest of us and so, we may wonder how such a proposal can come to the table. In other words, while the economics of anti-price-gouging is relatively straightforward, its political economy is more interesting.

I’ll only briefly comment on the former, economic aspect, as it has already been done by many commentators. Let’s start by noting that Harris’s proposed ban is not the same as calling for price controls. The idea is not to set prices in the whole industry (or, worse, in the whole economy) but rather to ban price increases in specific situations for their supposed unfairness. Some economists, such as Brian Albrecht on Substack, nonetheless argue that the margin is slim and that, ultimately, banning price-gouging entails giving bureaucrats the power to fix prices. Whether or not we agree doesn’t change much because the underlying economics is roughly the same. While the pro tanto basic economic principle is that we should not interfere with market prices, there are particular situations where a form or another of price control might eventually be granted. I see three such main situations:

· Sellers on a market are one way or another coordinating to fix prices at a (relatively) high level or (that comes to the same) agree to reduce their production and maintain supply at a low level.

· The government wants to prioritize some objectives that are viewed as of foremost importance for the country. This applies especially in the context of a war economy where it’s necessary to redirect most of the resources to the war effort as fast as possible.

· An exogenous (often natural) event leads to a sudden increase in demand for a (set of) good(s). As supply over the short run is fixed, prices are rising, which may be viewed as “unfair.”

For at least two of these three situations, this is however not so straightforward. If prices are high or rise because sellers are colluding, then the roots of the problem come from the market structure that is not competitive enough. While it may be justified to sanction companies that participate in collusion, the long-term solution is to make the market more competitive, rather than interfering with prices. Price increases due to a sudden increase in demand present a different problem. We know since at least a very famous article by Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler that individuals strongly resent price increases in such circumstances because they are viewed as unfair.[2] The event is random and not due to fault of their own, and so there is no reason that they should be harmed by a price increase. Symmetrically, suppliers don’t “deserve” the additional profits that happen only by chance. There is also an economic case against price increases in emergencies. After all, over the very short run (say, a day or two), the offer is anyway mostly fixed – graphically, the supply curve is a vertical line. Since the increase of the demand is only temporary, the price signal doesn’t signal anything. We don’t want the producers to increase their production in a week, we want to increase it now. If they can’t, there is no (economic) reason that they nonetheless benefit from higher prices.

But even here, the case for banning price-gouging is not straightforward. As John Cochrane notes, in most cases, we still want to incentivize producers to produce more in the near future and for that, prices must be allowed to increase. Moreover, even in an emergency situation, we still want that resources go to those who need or want them the most. Willingness to pay is a good proxy for measuring how much one wants or needs a good, but it can be effective only if prices are not interfered with. Sure, you can still say that this is unfair and that people who are not willing to pay the increased price (i.e., the poorest) should still be entitled to receive the good. That may be true (or sensible). In this case, just give them money – a point I had made in an old post published here. Anyway, as Cochrane puts it sharply, one basic economic principle is “don’t distort prices in order to transfer income.” There are other, more efficient ways, to do that.

Even if you don’t agree with all this, it remains that Harris’s ban proposal is anyway not targeted at one of those situations. There are good indications that the surge in food and grocery prices is related to economic fundamentals (tensions in supply chains), past policies (the monetary policies of central banks since the financial crisis), and exogenous non-economic events (the war in Ukraine). Because of all this, while production costs rose and constrained food supply, demand has kept increasing. The result is an increase in food prices. The ban cannot be justified on any economic ground.

Now, as I noted above, we may wonder why on Earth a candidate in a tight Presidential race comes with such a bad proposal. To understand this, we need to do some political economy. Assuming, plausibly, that Harris wants to be elected, her team is looking for proposals that have a decent chance of attracting additional voters, especially among those whose preference is not settled, even more if they belong to the swing states. The first possible explanation is that voters are (rationally) ignorant or even irrational – or at least, that Harris’s team assumed them to be so. Most voters don’t understand anything about economics, they don’t have the time and the interest to learn about it, but many of them will like a proposal that sounds to be designed to help them have some food on the table. This might be plausible, but my guess is that even mostly ignorant voters have the sense that blocking prices is overall harmful – though they may underestimate the harm it causes.

The second explanation is more subtle. Blocking price increases surely hurts the economy overall, but it may not harm everybody the same way. Consider a person who was just willing to pay the price asked for a good until now but who, after the price increase, can no longer afford it. This person will be negatively affected by the change of price anyway, so it may happen that she has nothing to lose by endorsing a policy of price control. Let me put the argument more graphically.

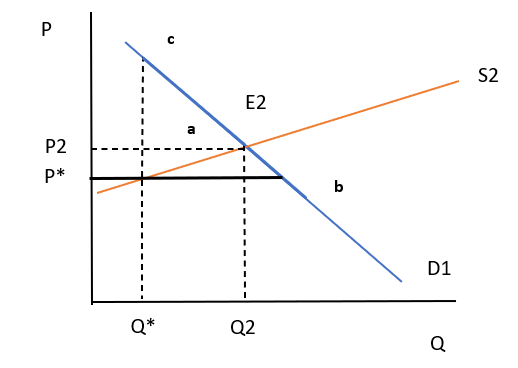

In this standard supply-and-demand graph, a shock reduces supply from S1 to S2. The market equilibrium changes from E1 to E2 with higher prices and lower quantities. The agents located on the segment ab of the demand schedule are negatively affected by the price increase as they no longer are willing (able) to pay for the good. Now, suppose that to fight this price increase, the government bans any increase above some level P*. Graphically, we have:

The graph makes it clear why blocking price increases is in general bad. By fixing the price at P*, supply is reduced at Q*, instead of Q2 if the government had not interfered. As a consequence, the agents on the segment cb of the demand schedule are negatively affected. But for the agent on the ab segment, the situation is not strictly worse than if the government had not interfered. In both cases, they no longer consume the good. Actually, for these agents, government interference might improve their situation. Indeed, if prices are blocked, then the allocation can no longer proceed based on people’s willingness to pay. At P*, a large number of agents are willing to pay for the good, but the quantity Q* available is not enough to satisfy everybody. Therefore, an alternative mechanism of allocation has to be found. For instance, the mechanism can work along a “first-arrived-first-served” rule. Or allocation can depend on people’s political or social connections. Or allocation might simply be random. Whatever the actual mechanism that is chosen, it is plausible that for at least some of the agents on the ab segment, their situation will strictly improve compared to the scenario where the price is allowed to increase. After all, in the latter case, they are sure that they will not buy the good. With an alternative allocation mechanism, they might have a strictly positive probability to receive it.

That doesn’t change the fact that overall, the government interference hurts the economy. It is even clearer in a general equilibrium setup, where interferences in a specific market create distortions elsewhere. Even those consumers who may benefit from price controls on a specific market are likely to be harmed overall. But this is not necessarily obvious to see.

There is however another reason why voters may be attracted by this kind of policies. In an interesting theoretical paper on the economic and political roots of populism, Daron Acemoglu, Georgy Egorov, and Konstantin Sonin develop a model where populist policies are accounted as an attempt to signal a candidate’s “honesty.”[3] Their model is thought to apply foremost to the left-wing populism of Latin American democracies but it seems to have partial relevance also here. The model assumes a two-candidate setup where one of the candidates is possibly corrupted by right-wing rich elites. Voters have however no way to be sure that this is actually the case. If one of the candidates is honest, it can be in her interest to choose “populist” policies that are on the left of the median voter to signal her honesty, i.e., the fact that her future policies will not be influenced by the elite’s interests. The gap between the populist platform and the median voter’s preferred platform constitutes the “populist gap.” In Acemoglu et al.’s model, this gap increases with the polarization between the median voter’s preferences and the interests of the elite, as the information is more imperfect, and with the perceived degree of corruption of candidates.

Harris’s proposal typically falls in the range of the “populist policies” that Acemoglu et al. target in their article. We can indeed interpret it as a way to signal that, if elected, she will not hesitate to fight against the private interests of a small economic elite that disregards the common good. It is even more sensible in a context where the opponent is someone who has obvious connections with the economic elite, notwithstanding his rhetoric. Of course, the model does not capture perfectly the situation. Trump himself largely defends populist policies and makes use of the rhetoric of corruption, though maybe in a slightly different sense. Moreover, as always with signaling strategies, there is the question of whether the signal is really credible – or if it is not ultimately only what economists call “cheap talk.” Specialists seem to agree that it is unlikely that even if Harris really wanted to pass the law, she would not be politically able to do so. The cost of agitating the prospect of banning price-gouging is therefore low for her. But these are subtleties that most voters may not perceive, which makes us fall back to the default assumption that voters are largely ignorant.

[1] A significant exception is Paul Krugman in a recent op-ed. But I wonder if Krugman would have written the same if the proposal had come from Trump.

[2] Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch, and Richard Thaler, “Fairness as a Constraint on Profit Seeking: Entitlements in the Market,” The American Economic Review 76, no. 4 (1986): 728–41.

[3] Daron Acemoglu, Georgy Egorov, and Konstantin Sonin, “A Political Theory of Populism,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128, no. 2 (2013): 771–805.

I very much agree that it would be much better to go after corporate concentration and actually enforce existing antitrust laws. My experience with Democrat friends and family has been that they do actually see anti price gouging laws as a way to fix things, and I think part of that is there are a lot of people who have seen the decades of "government will only make things worse" rhetoric lead to monopoly control of industries and higher prices for many goods. I think there are a lot of people who just want the government to be on the side of regular people rather than the wealthy and your populist analysis points to that.