The Sectarian Conundrum of Political Liberalism (Part 2)

Why We Should Agree to Disagree, But Only Up to a Point

This is the second post of a series about the “sectarian conundrum”. A third post will follow later. You can read the first post here.

This very ugly illustration is courtesy of Midjourney!

In the previous post, I characterized what I call the “sectarian conundrum of political liberalism”. As a reminder, it reads like this:

Sectarian Conundrum of Political Liberalism. According to political liberalism, legitimacy depends on the public justification of laws and rules. But a liberal society may need to be sectarian, i.e., to restrict the requirement of public justification to only a subset of the population. In this case, laws and rules can never be fully legitimate.

This conundrum points out a tension in the broad research program of political liberalism that is created by the requirement of public justification. One of the basic tenets of political liberalism is that the legitimacy of coercive laws and more generally the authority of any moral rules depend on the fact that laws and rules are justified by reasons that everyone is or could share/endorse/accept. However, while the public justification requirement is thought to be maximally inclusive – the idea is that no one is coerced for reasons they reject or view as unacceptable – it can lead to instability and conflict in morally diverse and pluralistic societies. The risk is that public justification can be achieved only by excluding a part of the population from its scope and/or by severely restricting the range of reasons that can be used. This is what I call sectarianism. In the first post, I argued that the so-called “internal conception” of political liberalism fails to satisfactorily answer the conundrum by reducing public justification to a mostly formal exercise of coherence within a population of reasonable persons. In this second post, I discuss a radically different approach within the public reason liberalism tradition, sometimes called the “New Diversity Theory” (NDT).

NDT has been largely pioneered by the late Gerald Gaus and has since then been developed by a dynamic group of young American political philosophers, most of them former students of Gaus.[1] What follows is a simplified description of NDT – this research program is itself diverse with many subtle variations that are not relevant here.[2] My main point is that while NDT improves upon the internal conception of political liberalism by trying to solve the conundrum, it doesn’t answer it in a convincing way because it underestimates the need for social cohesion based on mutually shareable and acceptable reasons.

A key tenet of NDT is indeed that public justification can be achieved even if “members of the public” do not share/accept/endorse the same reasons for a given rule. What matters is that each person agrees to follow a given rule for some reason that they consider, from their own point of view, as valid. These reasons can be radically different, or even inconsistent, this is irrelevant as long as everyone has some reason to follow the rule. This is why NDT is often said to rely on a convergence account of public reason, by contrast with the standard Rawlsian account which relies on the stronger notion of consensus.[3] Let’s illustrate the core ideas with a simple example.

Suppose that we have a population of five persons – Andrea, Beatrice, Chris, Denis, and Edgar. Each of these persons is endowed with what I will call an evaluative system B(i). For instance, B(Andrea) is the set of beliefs Andrea has about what is fair, good, what is permissible, what is forbidden, and so on. This set depends on two components: one or several evaluative standards E and a perspective P. The former corresponds to values based on which individuals determine what matters the most and how states of affairs should be ordered. For instance, Andrea may judge that it is better that economic resources should be distributed equally irrespective of people’s contributions rather than proportionally to these contributions. The latter refers to the way each person perceives the world. A significant example is given by abortion. Andrea, who we may assume is a committed catholic, can see a fetus as a living human being while Edgard, a convinced atheist, may just consider that it is nothing but a bunch of cells. While Andrea and Edgard may share an evaluative standard according to which preventing harm and saving lives is more important than bodily autonomy, their different perspectives will obviously lead to conflicting views about the permissibility of abortion.

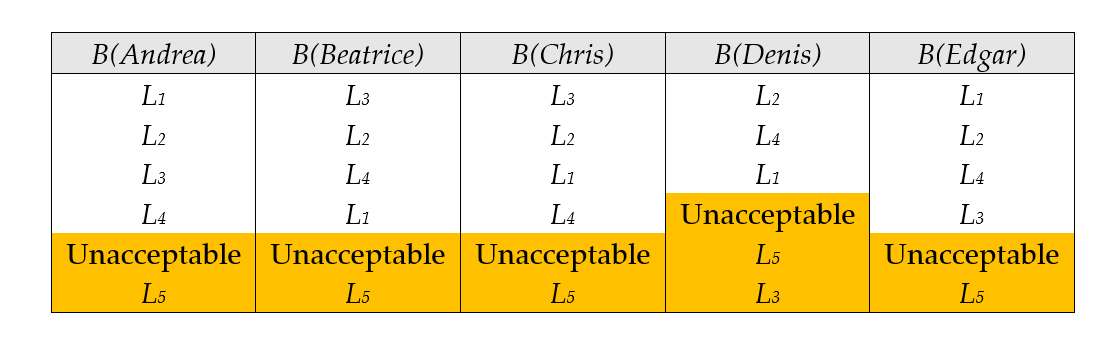

We can add to these two components an inference rule I based on which a person combines her evaluative standards and her perspective with the factual information at her disposal to form a judgment about rules. Here, we assume that individuals’ inference rules are error-free, meaning that they correctly interpret and understand the information and apply consistently their evaluative standards and perspectives to it. So far so good. Now, the key claim of NDT is that public justification only requires that rules are supported by mutually intelligible reasons. More specifically, let’s say that Andrea’s reason to endorse law L is intelligible to everyone else if and only if all members of the public recognize that Andrea’s evaluative system B(Andrea) supports L. In other words, B(Andrea) provides one or several reasons for L and this is acknowledged by every member of the public. Suppose, moreover, that evaluative systems rank alternative laws or rules, putting some of them below and others above an acceptability threshold. Here is an illustration:

In this example, all our members of the public view law L5 as unacceptable in light of their evaluative systems. So, there is no way this law can pass the public justification requirement. Interestingly, the same applies to law L3 in spite of the fact that Beatrice and Chris rank it as the best. The problem is that Denis regards it as unacceptable, so the other members of the public have to acknowledge that it can’t be justified to Denis. The three other laws are supported by mutually intelligible reasons. They form what Gaus calls the “socially eligible set”. Moreover, within this set, law L4 is strictly dominated by law L2. There are therefore no mutually intelligible reasons to prefer L4 to L2. Once L4 is excluded, we are left with L1 and L2, the “socially optimal set”. Which one will be adopted is left to specific evolutionary or social choice mechanisms. But it doesn’t really matter because both are publicly justified. Of course, Andrea and Edgar would prefer that L1 is adopted but even if it is not, they nonetheless have reasons to accept L2.

What is interesting here is that convergence by mutual intelligibility may obtain even if evaluative standards and perspectives widely differ in the population. People may not share any reason to accept a given law. What matters is that they agree that everyone has a reason to accept the law, even if these justificatory reasons may happen to be inconsistent. So, atheists and religious persons may agree that intentionally killing people should be strictly forbidden, even though they may disagree on why. In other words, public justification is consistent with the fact that persons can disagree about reasons. We can publicly agree that we disagree and still live together, or so it seems.

The convergence account seems to answer the sectarian conundrum. It is highly inclusive and permissive and, as long as at least one rule or law is viewed as acceptable by everyone, a stable agreement is reachable. “Unreasonable” or “illiberal” persons enter into the scope of public justification. There is no need to exclude anyone. The only requirement is that the reasons justifying the support for a law are consistent with people’s evaluative systems. We can formulate however several objections to this account and to NDT in general. Here are three, by increasing order of seriousness.

First, it might be argued that on this account, public justification is indeterminate. In other words, in general, several laws or rules will be publicly justified and so public reason is incomplete in the sense that it fails to arbitrate between competing rules. This can be an issue in so far as social choice mechanisms that select one of the rules can leave room for strategic and manipulative behavior.[4] The objection is weak, however. Rawlsian public reason also leaves room for indeterminacy. Moreover, because all the candidate rules are publicly justified anyway, nobody has a reason to reject the rule that is ultimately chosen.

The second objection is more serious. In highly diverse societies, it may happen that the socially eligible set is empty. That is, no rule may pass the test of mutually intelligible requirement. New diversity theorists tend to downplay this objection by claiming without much argument that this is highly unlikely. But this is not straightforward. Indeed, as soon as a citizen has a “defeater” against a law (i.e., an intelligible reason to reject the law), that law cannot be legitimately imposed. This turns out to have implications that contradict the intentions of new diversity theorists with regard to the place of religious beliefs in public justification. One of the concerns of new diversity theorists with Ralwsian public reason is indeed that it is inimical to religious believers. The convergence approach is thought to be more inclusive by authorizing bringing religious reasons to support or reject laws. But virtually every religious reason to support a law (e.g., a law banning abortion) will be defeated by a non-religious reason supporting an inconsistent law. It is not clear at all that religious persons would have a more appealing legal system under this approach to public justification.[5]

Of course, this works the other way around. Many laws will be opposed for religious reasons. And religion is only one of the many sources for finding defeaters to a broad range of laws. Beyond the relatively small set of laws and rules that can obviously be supported from several different perspectives such as laws forbidding killing or intentional harm, it is absolutely unclear that convergence will happen in highly diverse societies. If convergence does not happen, what is the solution? A possibility is to use selective exemptions. So, for instance, a law may apply except to those persons who claim to have an intelligible reason against it. It is clear however that it is unsustainable on a large scale. A real danger is to create resentment or even feed hatred between social groups. Moreover, this solution doesn’t work as soon as the law is related to the provision of public goods (or “bads”).[6]

This leads to the third objection. Even if on a case-by-case basis convergence may happen, some members of the public may consider that being too inclusive with respect to evaluative systems may carry future risks of social disruption. Indeed, until now, I’ve just assumed that the content of evaluative systems is irrelevant. But is it really the case? Indeed, we can argue that the reason why someone accepts a law does matter. It matters because I can find someone else’s reason to be offensive or based on wrong beliefs in the case at stake, but also because I suspect that these reasons will be used in the future to justify other laws that I expect to have reasons to reject. In other words, it is not true that any evaluative system can provide intelligible reasons. Once we recognize this, we are back to square one: how do we discriminate between evaluative systems? The temptation will be great to assume that some moral beliefs, though consistently derived, are based on unacceptable premises. Ejected through the door, sectarianism then returns from the window.

[1] Among the most notable contributors to this research program figure Brian Kogelmann, Michael Moehler, Ryan Muldoon, John Thrasher, and Kevin Vallier.

[2] I will put apart Moehler’s multilevel social contract approach, as I plan to discuss it in a separate post. On top of Gaus’s numerous books and articles, the following references are among the most significant contributions to NDT: Kevin Vallier, “Convergence and Consensus in Public Reason,” Public Affairs Quarterly 25, no. 4 (2011): 261–79.; Kevin Vallier and Ryan Muldoon, “In Public Reason, Diversity Trumps Coherence,” Journal of Political Philosophy 29, no. 2 (2021): 211–30.; John Thrasher and Kevin Vallier, “The Fragility of Consensus: Public Reason, Diversity and Stability,” European Journal of Philosophy 23, no. 4 (2015): 933–54.; Ryan Muldoon, Social Contract Theory for a Diverse World: Beyond Tolerance (Taylor & Francis, 2016).; John Thrasher, “Agreeing to Disagree: Diversity, Political Contractualism, and the Open Society,” The Journal of Politics 82, no. 3 (January 7, 2020): 1142–55.

[3] Another significant – but less relevant here – difference is that NDT postulates only a “mild” idealization of the members of the public. In general, to uncover the reasons that can justify a rule, it is only assumed that persons are free from cognitive biases. This is to be contrasted with the stronger idealization of the more Rawlsian approaches that rely on the concept of the veil of ignorance.

[4] In Gaus’s version of the convergence account, indeterminacy is rather solved by evolutionary mechanisms. The worry is then that a rule or law is selected for reasons that are completely unrelated to morality, e.g., social power or randomness. The answer is the same as in the main text.

[5] This argument is made in particular by Paul Billingham, “Consensus, Convergence, Restraint, and Religion,” Journal of Moral Philosophy 15, no. 3 (June 19, 2018): 345–61.

[6] Another possibility that I will not discuss here is to agree on a set of jurisdictional rights that define private spheres within which individuals are free to do what they want. To work, people have however to hold perspectives that agree on what belongs to each’s individual sphere. This leads again to the issue of externalities. Watching pornography may be thought to belong to anyone’s private sphere, but feminist perspectives may lead to consider that this is not the case because the consumption of pornography adversely affects the status of all women in society.