Institutional Unfathomability

Markets, Bureaucracy, and Algorithms

I've been exploring in this newsletter recently how people's growing inability to understand and control the institutions that shape their lives affects their political views (see here or here for instance). Two phenomena concur to produce this state of affairs. First, the social world is increasingly complex. Economies are more interconnected than ever, so much so that an American president can credibly threaten to shut down the entire economy of a neighboring country. Modern technologies have increased the speed and the amount of information that can travel from one end of the world to the other. However, information is not knowledge. Rather than empowering individuals, it can create confusion, deception, and either epistemic nihilism or naive credulity. As military threats and public good problems increase in scope, the world becomes smaller and all its parts highly interconnected. As the geopolitics specialist Robert D. Kaplan noted in a recent book, the world increasingly looks like a “global Weimar” with all the uncertainty and instability that characterized the interwar German republic.[1]

Second, social relations are increasingly impersonal. This is not new, as it has been a constitutive feature of the “open society” as liberal scholars like Friedrich Hayek and Karl Popper have characterized it. However, it has accelerated with the emergence of the internet and then social networks. This emergence has favored the growth of ever more distant social relationships between individuals who know nothing of each other but their pseudonyms. When social relations are predominantly impersonal, individuals have to rely on general rules to coordinate and cooperate, rather than on personal and intimate knowledge about others. In some respects, impersonality is at the root of social complexity. Humans are quite limited in the number of personal relations that they can sustain.[2] By becoming more impersonal, social relations have multiplied, contributing to the growing complexity of the social world.

Many positive aspects do exist in complexity and impersonality. The worldwide extension of markets, which is partly the result of economic globalization, has permitted a deepening of the division of labor and more gains from trade. Many economic and social innovations that have been clearly beneficial are tightly related to the new possibilities of cooperation offered by growing interconnectedness. The increasingly impersonal nature of social relations has helped many people escape situations of structural domination where one’s rights and liberties are attached to one’s status. It has considerably loosened the ties of social pressure that restrain individuals’ freedom in small communities.

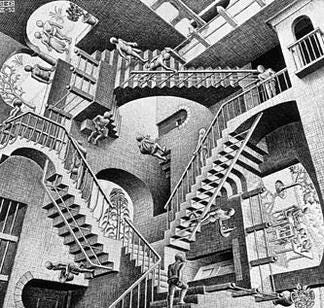

M.C. Escher, Relativity (1953)

However, complexity and impersonality entail less control over social events. This is one of the few paradoxes of modernity. On the one hand, widespread education and the constitutional recognition of rights and liberties to everyone in liberal democracies have undoubtedly helped to make individuals more autonomous. As far as their personal affairs are concerned, the modern individual has been empowered. They can decide whom to marry, whether to have children, with whom to work, how to use their spare time, and so on. On the other hand, it has never been so obvious that the modern individual is powerless regarding what is happening outside their small sphere of individual sovereignty. For decades if not for centuries, representative democracy has built on a myth (some would say a lie), that people —the People— are sovereign and can control, through political means, everything that has to deal with the affairs of the polity they belong to. This has never been the case in reality, but the difference today is that individuals have more abilities and resources to realize it. Probably, many of us could accept this powerlessness by retreating into our personal sphere. However, beyond the fact that this opens the way to new forms of tyranny as Benjamin Constant and Alexis de Tocqueville warned, the modern individual cannot be isolated from the social forces that affect not only the world but also their life. This is another myth, or lie, of liberal democracy—that you can be totally free in the purely negative sense. This myth is, in many respects, the cause of the otherwise unintelligible libertarian support for authoritarian leaders.

For better or worse, this lack of control is deemed to remain in any “post-modern” world that doesn’t renounce all the benefits brought by social complexity and impersonality. The challenge for liberal democracies is to imagine, design, and implement institutions at various scales (global, regional, national) that give some control back to individuals within the limits of what is physically and socially feasible. This must be done while taming both the negative external effects that affect human communities (e.g., climate change) and the populist excesses that inevitably happen when we forget that a proper democracy must work within a framework of constitutional rules that justifiably limits what the People can do.

A significant obstacle in this endeavor is, however, that it is increasingly difficult, including for the political and intellectual elite, to fully understand the mechanisms that are behind the economic and social outcomes that so deeply affect people’s lives. This may seem paradoxical as our scientific knowledge of the world keeps on growing. Just compare how our understanding of viruses and epidemics has progressed between the Spanish flu pandemic and the recent COVID pandemic. It’s only after the pandemic that scientists identified that what caused the symptoms of the Spanish flu was a virus. Less than a year after the start of the COVID, effective vaccines were already produced and distributed across (parts of) the world. However, progress is less obvious regarding our understanding of human-made events.

This is not to say that social sciences, including economics, have not progressed. At least in some very specific domains such as monetary mechanisms and policies, we know and understand way more today than a century ago. Indeed, a similar comparison can be made between the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Great Recession of the 2010s, as the one between the Spanish flu and the COVID pandemic. There is reason to think that, in the latter case, our improved understanding of monetary mechanisms helped to lessen the effects of a very serious and potentially deadly financial crisis.

However, the difference between natural and man-made events is that the latter grows in complexity as our global knowledge progresses. The more we know, the more we are able to design institutions and tools that increase social complexity and impersonality. Consider the continuous growth of complexity in the financial industry. This growth has been largely engineered—which doesn’t mean that it is fully intentional. Knowledge of computer science and economics has contributed to the development of new practices (e.g., high-frequency trading) that make the operations of financial markets barely understandable. This unavoidably has repercussions on regulation; you can hardly design and implement an appropriate regulation if you don’t understand the phenomenon that you are trying to regulate. With the exception of a few economists and professionals, nobody really understands how financial markets work beyond general principles and mechanisms.

At a more general level, the relationship between the growth of knowledge and increasing social complexity and impersonality can be identified with the development of markets and bureaucracies. Markets and bureaucracies are institutions, i.e., sets of social rules that define what individuals can, cannot, should, or must do in specific circumstances. Like all institutions, they help individuals coordinate and cooperate, especially because they allow them to form expectations about what others are likely to do. For instance, in France, you can confidently enter into a shop with Euro bills (or a credit card) to exchange them for some goods. You strongly believe, and in general, you’re right, that the shopkeeper will accept to sell their products in exchange for your bills. Similarly, you can be assured that if you want to renew your passport, you just have to bring the documents that are mentioned on some official list edited by the Ministry of Interior.

Markets and bureaucracies are complex institutions whose development has been permitted by the growth of scientific, especially technical, knowledge. The invention of double-entry accounting in the 14th century has rationalized the management and organization of productive activities. The emergence of new techniques to produce silver and gold coins and to make counterfeit money more difficult to produce has facilitated market transactions. Increasing capacities in data storage have permitted the expansion of bureaucratic monitoring and efficiency gains in bureaucratic procedures.

As markets and bureaucracies were expanding, social relations were becoming more impersonal and more complex. Just as we don’t have to know how an engine works to drive a car, we are using money, doing market transactions, and fulfilling bureaucratic procedures without exactly understanding all the operations that take place in the background. Economic, but also legal, and administrative knowledge are increasingly dispersed. As a result, it has become impossible for a single individual or organization, including the state, to master the entirety of the knowledge required to understand how institutions and society work.

Some of the consequences are well-known. Planning, whether economic[3] or administrative,[4] routinely generates nonintentional and unanticipated adverse outcomes. The way individuals react to centralized attempts to enforce an allocation of resources or a normalization of behavior is difficult to predict because planners lack the required knowledge and understanding. Besides the state, all individuals and organizations are facing the same problem of being very often unable to predict and, more fundamentally, to understand social dynamics. This can be a source of frustration and resentment, especially when this inability translates into the kind of powerlessness I’ve discussed above. Resentment emerges in particular when individuals fail to find any reason that justifies a given state of affairs, especially when they are primarily concerned. You can’t identify such reasons if you have difficulties understanding the phenomena that you’re observing. The alternatives are then limited. Most often, there is nothing better than picking randomly one or a few hypothetical reasons by identifying a scapegoat, endorsing myths or conspiracies, or blindly following some charismatic leader.

The challenge of “institutional unfathomability” is now being amplified by a new force: algorithms. As Yuval Noah Harari argues in his book Nexus, the widespread use of sophisticated algorithms in financial and medical decision-making is making our institutions even more opaque.[5] The individuals and organizations using these algorithms will increasingly be unable to explain how the output has been generated. This militates to the creation of what Harari calls a “right to an explanation,” but how such a right can be enforced is unclear. The absence of explanation will only contribute to stimulating, even more, the human brain in its quest for reason and justification, with the risk of feeding myths that themselves contribute to worldviews that encourage seeing the world through the lens of conflict and conspiracy rather than cooperation.

We would like to think that education is the straightforward response to this institutional unfathomability. However, this is unlikely to be the case. This issue is becoming more serious even though the general level of education has never been so high. More worryingly, some data suggest that humans may have “passed their peak brain power,” due to the very same technologies that make the social world increasingly harder to decipher. Reverting back to a simpler social world with more personal social relations within smaller communities is not really an option, not one that you can politically plan anyway. The only perspective is to keep trust in the fact that we can find and design institutions and rules that promote cooperative and mutually beneficial endeavors, even though we don’t fully understand their operations. This is what happened when impersonal markets and bureaucracies first emerged and contributed to an unprecedented improvement in living conditions in many parts of the world. Admittedly, this is also almost a myth because it is hardly possible to prove that what has been true in the past will still be true in the future. Let’s call it the “liberal quasi-myth.” Of all the myths available in the market for ideas, this is the only attractive one.

[1] Robert D. Kaplan, Waste Land: A World in Permanent Crisis (La Vergne: C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd, 2025).

[2] R. I. M. Dunbar, “Neocortex Size as a Constraint on Group Size in Primates,” Journal of Human Evolution 22, no. 6 (June 1, 1992): 469–93.

[3] F. A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom: Text And Documents--The Definitive Edition, New edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1945 [2007]).

[4] James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998 [2020]).

[5] Harari Yuval Noah, Nexus : A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI (London: RANDOM HOUSE UK, 2024).

Wonderful! If I may venture a couple of thoughts:

(1) The growing illegibility or unsurveyability of things incentivizes the use of signals and metrics as proxies for "what is going on" with the things: think of prices, grades, GDP, college rankings, number of clicks, etc. These proxies are designed to make things legible to centralized, bureaucratically arranged institutions. But, partly because of their usefulness for the interests of these institutions, these metrics come to be seen less as proxies and more as the thing itself, because they give the illusion of legibility or surveyablity. And individuals inside and outside of the institutions tend to adopt these proxies too, again partly because of their perceived usefulness for the interests of the institution. But the proxies are meant to abstract from all sorts of potentially relevant messiness, and might not reflect what we need to understand in order to actually understand the system. All of this is a long way of getting to this point: it's bad enough to feel out of control because of how opaque these systems are, but it might be worse to succumb to the illusion that you finally understand these opaque systems simply because you see how a collection of proxies might be related — all while the systems still remain out of your control.

(2) One could take your post to present some support for reviving and aiming for the old ideal from Catholic social teaching of subsidiarity, according to which wider or more distant spheres of authority and power exist to authorize and empower narrower and less distant spheres of authority and power. It's a way of redistributing *some* control downward, toward the local, where certain arrangements, or aspects of arrangements, are less insulated from popular contestation.