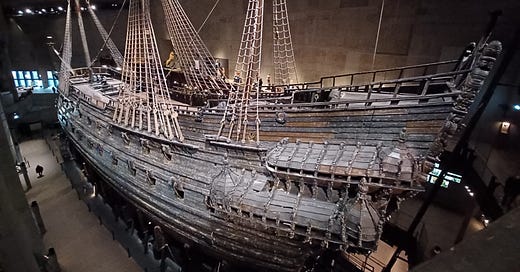

I’m just back from an extended weekend in Stockholm. I had great expectations (it was my first time there), and I’ve not been disappointed. We stayed in a hotel in Skeppsholmen, a small island southeast of downtown. Among the many remarkable places to be seen, there are of course the Vasamuseet and the Skansen. The city is lovely in general and the people there are very nice. It also has some great bookstores, the best (from my very subjective perspective) being Hedengrens where I found very nice English books on politics, philosophy, and economics that I haven’t seen elsewhere, including in bigger British or American bookstores.

In the Vasamuseet

The Nobel Prize

Anyway, as I like to do here sometimes, let’s take this as an excuse to discuss some themes more or less related to Sweden and Stockholm. I would like to briefly address two more particularly. The first is – obviously – the Nobel Prize in Economics. Daron Acemoglu was giving his banquet speech in Stockholm last week. The Nobel Prize in Economics (formally, the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel”) has been the subject of controversies for decades. Besides that economics was not among the disciplines mentioned in Nobel’s testament, critics insist that economics is either not a science or that the prize is more about ideology than science. Others sometimes note that there is no reason that among social sciences, economics is the only one to have “its” Nobel prize.

In France at least, this kind of criticism is like leaves falling in Autumn – you know that they will appear again the next time the prize is given. This year was no exception with an op-ed published by two historians in the French newspaper Le Monde. Now, I’ve explicitly argued in this newsletter that scientific prizes are in general of doubtful relevance and I still stand by this claim. Given the fact that the Economics Nobel Prize exists, I nonetheless found this op-ed unfair and misguided. I, therefore, take the opportunity to highlight the response I published in the very same newspaper a month and a half ago. Here is an extract that responds to the two historians’ criticisms according to which Acemoglu, Robinson, and Johnson have not been corroborated enough to deserve the Nobel Prize:[1]

“Should we then refrain from rewarding work which, over the last twenty years, has fuelled a wealth of research, some of which refutes, others confirming, the thesis of the essential role of institutions? It's true that the Nobel Prizes awarded in the so-called “hard” scientific disciplines tend to reward work that seems to mark an indisputable advance in knowledge by producing uncontroversial knowledge. Yet philosophy of science and epistemology teach us that, whatever the discipline, scientific knowledge is always provisional and open to question.

…

The work developed by Acemoglu, Robinson and Johnson over the last two decades is a good example of a research program. It is built around a strong hypothesis (the role of institutions, and more specifically property rights, in economic development), a theoretical framework proven by decades of economic research (rational choice theory), widely-accepted econometric methods and “auxiliary hypotheses” which are, in turn, subjected to evaluation through various historical case studies.

One can argue about the solidity of the results obtained in the light of historical knowledge. What cannot be denied, however, is the scope and influence of this research program in the discipline of economics, whether in the evolution of empirical and econometric methods for studying historical issues, or in the reinforcement of the idea (apparently simple, except for “hard-core” economists) that “institutions matter”.”

In the last paragraph of the op-ed, I note however that in light of the growing interdisciplinary nature of economics both regarding its methods and objects, there is no longer any good reason to restrict the prize to economics. The above reasoning indeed indicates that all social sciences can legitimately claim to be the home of contributions to knowledge that can equally pretend to receive this kind of prize with highly symbolic value.

Stockholm by night and under snow (on Kastellholmen, a small island next to Skeppsholmen)

The Unanimity Principle

Stockholm is the home of the notorious and influential “Stockholm school of economics” – not only the business school but more importantly the school of economic thought. The school’s most prominent members were Gunnar Myrdal (an economics Nobel Prize) and Bertil Ohlin. Both were influenced by Knut Wicksell who made distinguished contributions to value theory and theory of public finance. I’m far from being a specialist in Wicksell’s work – indeed I’ve never read him – but like many, I’m familiar with his name because he is extensively mentioned by another Nobel prize, James Buchanan, both in his solo writings and joint work with Gordon Tullock.[2]

Buchanan regularly appeals to Wicksell in the context of what can be called the “Unanimity Principle.” Wicksell in particular investigated how public goods can be provided through a fair tax system where the tax burden is fairly distributed according to the benefits each individual receives from the provision of the public good. It is in this context that Wicksell proposes the mechanism of unanimity to ensure that no one can rightfully complain that they are paying more than they are receiving benefits through the provision of the public good.

Herbert Simon’s Nobel Prize medal

Buchanan’s work in public finance, public goods, and later on constitutional political economy largely consists of a generalization of this insight. For instance, in The Limits of Liberty, Buchanan’s main political philosophy contribution, he argues that the “paradox of being governed,” can be solved by approximating the use of the unanimity rule both in the constitutional stage where property rights are allocated and in the “post-constitutional stage” where public goods are provided in the context of joint activities.[3] In the constitutional stage, individuals have a mutual interest in allocating property rights such as to limit expenses for predation and defense against predation. This mutual interest guarantees that a unanimous agreement over an allocation of property rights, taking the form of a “constitution,” can be found. Once the constitution is established, individuals can freely trade their property rights at a negotiated rate. At this post-constitutional stage, individuals presumably exchange rights only when it is in their interest to do so. This is indeed a fundamental insight of economic analysis. Voluntarily bilateral exchanges are Pareto-improving and are in this sense a particular application of the Unanimity Principle. As Milton Friedman puts it in Capitalism and Freedom, the market system permits “unanimity without conformity.”[4] A mechanism of free and voluntary mutually advantageous exchanges of rights on goods is in principle the only way to implement unanimous agreement while properly respecting the diversity of individuals’ preferences and beliefs. As I have suggested elsewhere, we may even want to extend the logic further and allow for voluntary exchanges of all kinds of rights, not only property rights.

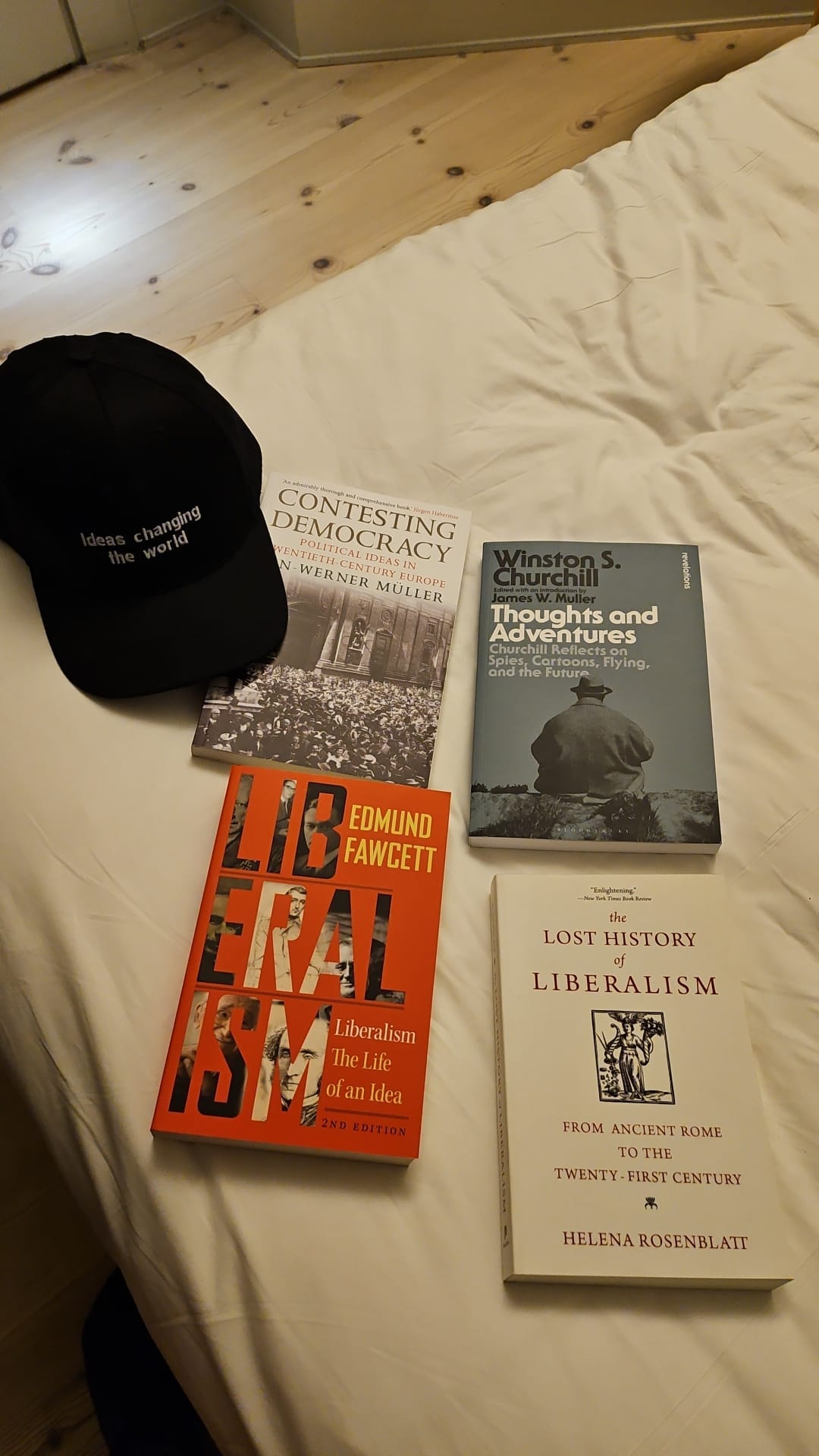

I found a lot of books in Hedengrens!

Now, there are of course significant exceptions to this general principle. If non-economic rights (i.e., rights other than property rights) are not alienable, there may be conflicts between unanimity (defined as the Pareto criterion) and those non-economic rights.[5] Also, and more significantly, “unanimity without conformity” becomes more difficult to achieve when external effects are at play, especially in the case of joint consumption or production activities (what is generally called “public goods”). With externalities, the mutually advantageous economic exchange between A and B may have adverse effects on C, meaning that while A and B have no reason to oppose the exchange, C is likely to have one. Unanimity is then no longer guaranteed. In this context, non-unanimous and thus coercive mechanisms such as a tax system might be needed to fund for instance the provision of public goods. Ideally, you may want something like Wicksell’s tax scheme where individuals give according to their willingness to pay. Such a tax scheme is however not incentive-compatible, i.e., rational individuals will in general lie and underestimate their willingness to pay.

One of the many Stockholm’s Christmas markets

Because of that, it is difficult to stick with the requirement of unanimity. On pragmatic terms, Buchanan concedes that a form or another of majority rule is likely to be needed in the post-constitutional stage. However, this majority rule should not operate in a total vacuum. The constitution agreed on at the constitutional stage must contain a condition that determines in advance which tax schemes (for instance) will be allowed, if adopted by a majority, to fund public goods. Some individuals will happen to be net losers with a specific tax scheme, but this is unproblematic as long as they have previously agreed on a constitution that stipulates that the tax scheme could eventually be adopted. Why these individuals would agree on such a constitution then? As Buchanan and Tullock put it, constitutional choices are generally made behind a “veil of uncertainty” and a constitutional agreement over the range of tax schemes permitted can be viewed as an agreement over an insurance mechanism.

A similar analysis may be relevant regarding the functioning of the European Union.[6] The unanimity rule prevails for a large number of decision problems. Member countries are reluctant to give up this rule as it would otherwise seem to entail a concession regarding their sovereignty. On the other hand, the requirement of unanimity is an undisputable source of inefficiency because it slows down the decision process and makes it more costly. The problem can be viewed differently, however. By entering into the EU, countries implicitly agree to a “constitution” and therefore agree to submit to decision rules that may not respect unanimity. As in the case of tax schemes, the EU constitution should allow for majoritarian decision rules that will lead, on some occasions, some countries to be “net losers.” This is unproblematic as long as everybody has consented to these rules in advance. Unfortunately, the historical and legal context through which the EU has been constructed does not allow for this interpretation. So much the worse for the EU. Unanimity is a worthy ideal but at times it can be a hindrance.

In the end, I brought “only” four books

[1] Translation from French courtesy of DeepL.

[2] See in particular James M. Buchanan, The Limits of Liberty: Between Anarchy and Leviathan (University of Chicago Press, 1975). James M. Buchanan and Gordon Tullock, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Inc, 1999).

[3] Buchanan, The Limits of Liberty.

[4] Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom: Fortieth Anniversary Edition, First Edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962 [2002]).

[5] Amartya Sen, “The Impossibility of a Paretian Liberal,” Journal of Political Economy 78, no. 1 (January 1, 1970): 152–57.

[6] See Garett Jones, 10% Less Democracy: Why You Should Trust Elites a Little More and the Masses a Little Less, 1er édition (Stanford University Press, 2020), 159-62.