The Game Theory of French Snap Elections

And What it Says About the Justification of Democracy

Since French President Emmanuel Macron announced the dissolution of the Assemblée nationale (the French lower parliamentary chamber) in the wake of the large victory of the far-right in the European elections, a large majority of the French people have been living in anguish. For the first time since the Second World War and the Vichy regime, there were serious prospects that nationalist extremists would arrive at power by earning an absolute majority at the snap elections. The French political system is indeed made in such a way that, though executive powers are in normal times largely concentrated in the hands of the President, (s)he cannot govern without a majority at the AN. If (s)he doesn’t have a majority, (s)he has no choice but to nominate a prime minister who has a decent chance to get the approval of the parliament and, practically speaking, it is then the prime minister and his or her government that govern. The concerns were amplified by the results of the first round last week that put the Rassemblement National (RN, the far-right party of Le Pen) well ahead of the left and centrist coalitions.

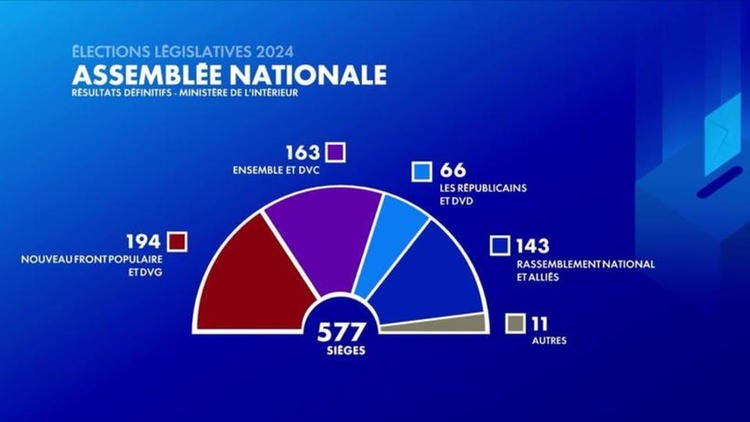

Yesterday’s results have been received as a relief, not only by French people. Far from obtaining an absolute majority (289 out of 577 seats), the RN fell to third place with 126 seats (+ 17 from the right party Les Républicains who rallied the RN). The governing coalition finally did far better than expected with 158 seats, though it still lost almost 100 seats. The left coalition of the Nouveau front de gauche clinches first place with 182 seats. Though it is now a certainty that the far right will not rise to power following these elections, it is still unclear what will happen next. No party or coalition is even close to the absolute majority. In practice, that means that whoever is the next prime minister, his/her government will have to pass laws using the infamous 49.3 article that permits skipping a vote at the parliament and face the risk of a “motion de censure” forcing its resignation. That does not necessarily mean that France will be “ungovernable” for the next three years (there are other means to govern than law), but it will significantly impede political action in the immediate future.

These results may seem surprising in light of the success of the far-right parties in the European elections and the first round of the legislative elections last week. Though polls were not giving the RN an absolute majority, most predictions were converging toward the 210-250 seats range, putting the RN ahead of the two coalitions. Does it mean that voters changed their minds in the meantime? Well, yes and no. Contrary to European elections and to what is the case in many Western democracies, French legislative elections do not use the proportional rule. Instead, votes proceed separately in each of the 577 constituencies with a separate list of candidates. In the first round, if a candidate gathers more than 50% votes of the constituency electorate (not of the actual voters), she is directly elected. Otherwise, a second round takes place where all the candidates who received more than 12,5% votes of the constituency electorate are qualified. In the second round, the candidate who comes ahead wins, even if she doesn’t have the absolute majority.

Two important factors account for what happened in Yesterday’s vote. First, the turnout in the first round was relatively high, above 67%, compared to less than 50% two years ago. Mechanically, that implies that the number of constituencies where 3 or even sometimes 4 candidates are qualified for the second round is relatively high. Second, the nature of the political landscape entailed that in many constituencies, the second round would involve a candidate from the left coalition, one from the far-right, and one from the center coalition. If in all constituencies, all the candidates qualified had effectively maintained their candidacy, the RN would have probably won in many cases as its candidates had arrived first in the first round. The RN would then probably have earned around 250 seats, if not 300. What happened instead is that in more than 200 constituencies, a tacit or explicit agreement between the non-RN candidates led those who were qualified at the third and fourth spots to resign and “offer” their votes to the remaining “republican” candidate. This strategy has been quite effective: in many constituencies, the majority of the votes received by non-RN candidates indeed added up, which explains why RN candidates were beaten even though they were ahead in the first round.

What is remarkable here is that since the elections in each constituency are independent, the decision of the parties to resign in those situations where three or more candidates were qualified was not centralized. As it happened, in slightly above 100 constituencies, several “republican” candidates competed in the second round, often leading to the election of the far-right candidate. From a game-theoretic perspective, the left and center coalitions were engaged in what superficially may look like a kind of prisoner’s dilemma. Basically, each coalition would have ideally kept its candidate in the competition, hoping that the other coalition resigns. In many cases, in case the other coalition stayed in the course, the election was anyway lost, meaning that staying or resigning would not make much difference – except for the fact if the former, the RN candidate was likely to win. A simple 2x2 matrix can help to see things more clearly:

The game is actually not a prisoner’s dilemma. Maintaining one’s candidate is a strictly dominant strategy for each coalition. There is nothing to gain by resigning and maintaining one’s candidate may eventually permit winning.[1] The “socially optimal” outcomes for (most) citizens are those where only one of the two coalitions maintains its candidate but the logic of the strategic interaction suggests that this will not happen – the only Nash equilibrium is where both coalitions maintain their candidates in the second round.

Now, though elections in each constituency are formally independent, the corresponding games are not. The fact that there are several hundred games of this kind means that the coalitions can eventually play conditional strategies of the kind “if you desist in constituency A, I will desist in constituency B.” This gives rise to a supergame where coalitions can potentially share (not necessarily equally) the benefits of a “republican agreement”:

In the game above, we assume that both coalitions can roughly split the benefits of the agreement equally and that in case no agreement is concluded, they play their dominant strategy. Now, we have a second Nash equilibrium where both coalitions play according to the republican agreement. Not only is this outcome presumably preferable for citizens (many of them at least), but it is also better for the coalitions.

The implementation of the agreement has had a counterintuitive effect. When you look at the shares of vote for each party/coalition, you’ll see that the RN and its allies are still far ahead with around 37% of votes, against 27% and 22% for the left and center coalitions respectively (see the graph below, found on Marginal Revolution). You might be tempted to conclude that the outcome is anti-democratic, and this is exactly what RN leaders said yesterday. This is also probably what RN voters think. From these voters’ perspectives, the elections are likely to appear to have been “stolen” by the strategic manipulations of the mainstream parties, willing to make all kinds of concessions just to stay in power. But this is only true from a populist account of democracy. As the political scientist William Riker defines it, the populist account of democracy grounds the legitimacy of democratic institutions in their ability to embody the will of the people in the actions of officials.[2] On this view, elections and the actions of officials must reflect the “general will” of the citizenry. From this perspective, the kind of agreement that was at play in the French elections yesterday is problematic because it seems to create a discrepancy between what “the people” want and the outcome of the electoral process.

However, there are good reasons to reject the populist conception, starting with the results of social choice theory that precisely show that the general will is most of the time ill-defined. Instead, what Riker calls the liberal conception of democracy holds that voting is foremost a tool to control officials. In a democracy, we don’t want elections and policies to reflect an elusive collective will. We want mechanisms that put limits on the power of those in charge and that incentivize them to be responsive to the diversity of values, beliefs, and judgments of the population. In this sense, yesterday’s results should be appreciated positively because they generate a situation in which, one way or another, governing parties will have to make compromises in a context where their actions will be severely constrained.

We should not celebrate too much, however. Beyond the risk of political paralysis – which is a downside of constraining political power – the resulting equilibrium may be highly unstable. In particular, many citizens do endorse the populist interpretation of democracy. From their perspective, the electoral outcome and the eventual policies that result from it will lack the required legitimacy. That will undoubtedly feed the populist sentiment, in a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. The next Presidential elections are in three years. In the meantime, whoever will govern, they will have the huge responsibility to convince as many people as possible that the republican agreement is more than a mere political tactic. Otherwise, next time, the trick will not work.

[1] The assumption here is that each coalition is only maximizing its number of seats at the Parliament, not minimizing the number of seats for the RN.

[2] William H. Riker, Liberalism Against Populism: A Confrontation Between the Theory of Democracy and the Theory of Social Choice (Prospect Heights, Ill: Waveland Pr Inc, 1987), p. 11.

I found the analysis done very interesting. I would like to know if the French elections could be analyzed by applying the choice of policy platform model, and calculate what the equilibrium would be.

Last week, a Jewish girl in France was gang-raped by a group of Moroccans. This is just the latest in a long list of similar acts committed against French Jews by 'French' Muslims. Absolutely everyone knows by now that the only way to stop this is through the FN. The LFI barely even bother to pretend they do not support these attacks, and everyone knows they will now become more frequent. Tens of thousands of Jews will now flee the country. Whatever we can say about that, we can't say that the French didn't make this decision with their eyes open.